When the temperature climbs above 24°C (75.2°F), something dangerous happens to people who use drugs: their risk of overdose goes up - not because they use more, but because their body can’t handle what’s already in it. Heat doesn’t just make you sweaty. It changes how drugs work inside you, and for some, that difference is deadly.

Why Heat Makes Overdose More Likely

Your body is always trying to stay at 37°C. When it gets hot, it works harder: your heart pumps faster, you sweat more, and your blood vessels open up to release heat. But if you’re using stimulants like cocaine or meth, your heart is already racing - 30 to 50% faster than normal. Add heat, and you’re pushing your cardiovascular system past its limit. One study from New York City found that for every week the temperature stayed above 24°C, overdose deaths jumped significantly. Cocaine-related deaths were the most strongly tied to heat.

Dehydration plays a huge role too. Losing just 2% of your body weight in water - which happens easily in a heatwave - concentrates drugs in your bloodstream. That means the same dose you took last week could now feel like 15-20% stronger. It’s not that you took more. Your body just got less fluid to dilute it.

For opioid users, heat is just as dangerous. High temperatures reduce your body’s ability to adjust breathing when opioids slow it down. Studies show respiratory compensation drops by 12-18% in heat, meaning the line between a safe dose and a fatal one gets thinner. And if you’re already feeling dizzy or confused from heat exhaustion, you’re less likely to recognize the warning signs - nausea, vomiting, extreme fatigue - before it’s too late.

Who’s Most at Risk

This isn’t just about people who use drugs. It’s about people who have no place to cool off. In the U.S., nearly 600,000 people experience homelessness on any given night. About 38% of them also have a substance use disorder. Many shelters won’t let people in if they’re actively using. Air-conditioned public spaces like libraries or malls often turn people away for being “disruptive.”

People on medications for mental health are also at higher risk. About 70% of antipsychotics and 45% of antidepressants become less effective or cause worse side effects in extreme heat. That means someone managing depression or psychosis might feel worse, use more drugs to cope, and then get hit with a double hit - worsening mental health and a body that can’t handle the heat.

And it’s not just big cities. Places like Oregon and Washington - where summer highs rarely top 80°F - saw overdose risk spike 3.7 times higher during the 2021 heat dome than in hotter states like Arizona. Why? Because people there aren’t used to it. Their bodies didn’t have time to adapt.

What You Can Do: Practical Harm Reduction Steps

If you or someone you know uses drugs, here’s what actually helps during a heatwave:

- Reduce your dose - by 25-30%. Even if you’ve used the same amount for years, heat changes how your body processes it. Lowering your dose isn’t weakness - it’s survival.

- Drink water - but not too fast. The CDC recommends one cup (8 oz) every 20 minutes. Cool water (50-60°F) works best. Avoid alcohol and caffeine - they make dehydration worse. Electrolyte packets (like those used by athletes) help replace what you lose through sweat.

- Don’t use alone. If you’re using, have someone nearby who knows how to use naloxone. If you’re with someone who’s using, stay with them. Watch for signs of trouble: confusion, vomiting, slow breathing, or skin that’s hot and dry.

- Find shade or cooling centers. Many cities now have “cooling stations” open during heat advisories. Some are co-located with harm reduction services - places where you can get water, rest, and naloxone without being judged. Vancouver’s program cut heat-related overdose deaths by 34% by doing exactly this.

- Check on others. If you know someone who’s homeless or uses drugs, ask if they have water, shade, or access to air conditioning. A simple check-in can save a life.

What Communities and Providers Need to Do

Individual actions matter, but systemic change is critical. Only 12 out of 50 U.S. states have officially included people who use drugs in their heat emergency plans. That’s a failure of policy.

Health clinics should be screening patients using a tool called CHILL’D-Out - a simple questionnaire that asks about housing, medications, heart conditions, and drug use during hot weather. If someone says they don’t have AC, they’re on an antipsychotic, and they use opioids - they need a plan before the next heatwave hits.

Outreach teams are already doing this work. In Philadelphia, harm reduction workers hand out cooling kits with misting towels, electrolytes, and info cards. In Maricopa County, Arizona, volunteers trained in naloxone made over 12,000 wellness checks during the 2022 heat season and intervened in 287 overdoses.

But there are still barriers. Police in some cities have confiscated cooling supplies from outreach workers. Shelters still turn people away. Until these policies change, people will keep dying.

The Bigger Picture

Climate change isn’t coming. It’s here. By 2050, the U.S. could see 20 to 30 more days each year above the 24°C overdose risk threshold. The Biden administration just allocated $50 million to fix this - but only if states update their heat plans by December 2025.

What we’re seeing isn’t just a public health issue. It’s a justice issue. People who use drugs aren’t “high-risk” because of their choices. They’re high-risk because society leaves them without shelter, without care, and without dignity when the temperature rises.

The solution isn’t just more naloxone. It’s air-conditioned spaces. It’s trained outreach workers. It’s policies that say: Everyone deserves to survive the heat.

What to Do If You See Someone in Distress

- If someone is unresponsive, not breathing, or has blue lips - call 911 immediately.

- Give naloxone if you have it. It works for opioid overdoses, even during heat events.

- Move them to shade or a cooler area. Remove excess clothing.

- Try to cool them down with wet cloths or misting - but don’t put ice directly on skin.

- Stay with them until help arrives. Don’t leave them alone.

Can heat make a drug overdose worse even if I’m not using heavily?

Yes. Even small amounts of drugs can become dangerous in heat because your body’s ability to process them changes. Dehydration concentrates drugs in your blood, and heat strains your heart and lungs. You don’t need to be using a lot - just one dose, combined with high temperatures, can be enough to trigger an overdose.

Does naloxone work during heat-related overdoses?

Naloxone only reverses opioid overdoses. If someone overdoses from cocaine, meth, or another stimulant during a heatwave, naloxone won’t help. But it’s still critical to have on hand because many people use multiple drugs. If you’re unsure what was used, give naloxone anyway - it won’t harm someone who didn’t use opioids. Always call 911.

Why do some shelters turn away people during heatwaves?

Many shelters have policies against active drug use, fearing safety issues or liability. But this leaves the most vulnerable - people with substance use disorders, no home, and no AC - outside when it’s hottest. Some cities are changing this. Vancouver, for example, now allows drug use in designated areas of cooling centers. Safety doesn’t require punishment - it requires compassion and planning.

Are there free cooling kits available?

Yes. In cities like Philadelphia, New York, and Seattle, harm reduction organizations distribute free cooling kits during summer months. They include electrolyte packets, misting towels, water bottles, and info on where to find cooling centers. You can ask at local syringe exchanges, clinics, or community centers. No ID or proof of need is required.

Can medications for mental health increase overdose risk in heat?

Yes. About 70% of antipsychotics and 45% of antidepressants become less effective or cause dangerous side effects in extreme heat. This can lead people to use more drugs to cope with worsening symptoms - creating a cycle that increases overdose risk. If you’re on medication and it’s getting hot, talk to your provider about adjusting your plan before the next heatwave.

What Comes Next

By 2025, every state in the U.S. will be required to include overdose risk in its heat emergency plan - if the federal funding is used as intended. That means training first responders, opening cooling centers that accept people who use drugs, and equipping outreach teams with the tools they need.

Until then, the work falls to communities. Check on your neighbor. Carry naloxone. Share water. Don’t assume someone else will act. In a heatwave, survival isn’t about luck - it’s about who shows up.

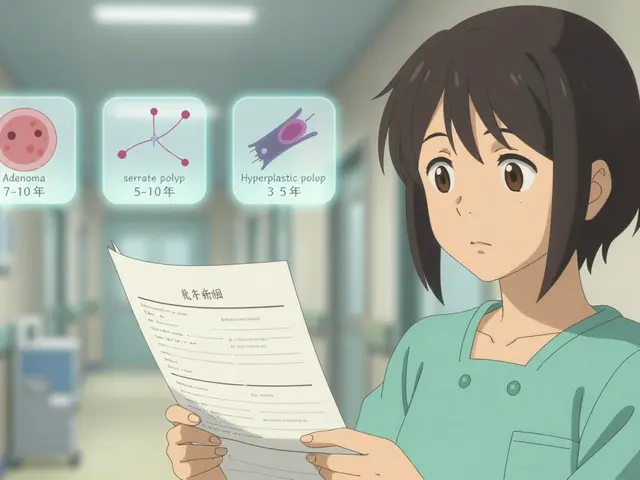

Repeat Colonoscopy: What Your Surveillance Interval Should Be After Polyp Removal

Repeat Colonoscopy: What Your Surveillance Interval Should Be After Polyp Removal

Velpatasvir and Hepatitis C: What’s New in Treatment and Research

Velpatasvir and Hepatitis C: What’s New in Treatment and Research

Vitamin E and Warfarin: What You Need to Know About the Bleeding Risk

Vitamin E and Warfarin: What You Need to Know About the Bleeding Risk

How to Appeal a Prior Authorization Denial for Your Medication

How to Appeal a Prior Authorization Denial for Your Medication

Skin Inflammation Explained: Causes, Signs & Effective Treatments

Skin Inflammation Explained: Causes, Signs & Effective Treatments

Scott Conner

February 10, 2026 AT 08:07Randy Harkins

February 10, 2026 AT 18:01Jessica Klaar

February 11, 2026 AT 11:31Tatiana Barbosa

February 12, 2026 AT 12:36Tasha Lake

February 13, 2026 AT 14:24John McDonald

February 15, 2026 AT 07:31Chelsea Cook

February 16, 2026 AT 15:58Lyle Whyatt

February 17, 2026 AT 06:54Karianne Jackson

February 17, 2026 AT 22:19John Sonnenberg

February 18, 2026 AT 13:04glenn mendoza

February 19, 2026 AT 04:08Tricia O'Sullivan

February 20, 2026 AT 17:50PAUL MCQUEEN

February 22, 2026 AT 01:38Susan Kwan

February 23, 2026 AT 04:35