Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., yet they account for just 23% of total drug spending. That’s not an accident. It’s the result of a system designed to let competition drive prices down-without government setting fixed prices. If you’ve ever paid $4 for a month’s supply of metformin or sertraline, you’re seeing this system work. But how did we get here? And why don’t the government’s latest drug price laws touch generics at all?

Why Generic Drugs Don’t Need Price Caps

Branded drugs cost tens of thousands of dollars because companies spend billions on research, clinical trials, and marketing-and they have a monopoly until the patent expires. Generics don’t have that burden. Once a patent runs out, other manufacturers can copy the drug. They don’t need to repeat expensive safety studies. They just need to prove their version works the same way. That’s called bioequivalence. And once even one other company enters the market, prices start falling fast.

According to the FDA, when a generic version hits the market, prices drop by about 75% within six months. If three or more companies start selling the same generic, prices tumble to just 10-15% of the original brand’s cost. That’s not speculation-it’s data from a 2021 FTC study. And here’s the kicker: in markets with strong competition, there’s almost no evidence that prices rise unfairly. The system works because it’s built on competition, not control.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Secret Engine Behind Low Generic Prices

The foundation of today’s generic drug market wasn’t created by a price control law. It was created by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before this law, generic manufacturers had to run full clinical trials to prove their drugs were safe and effective-just like the original maker. That cost $100 million or more. Most couldn’t afford it.

Hatch-Waxman changed that. It let generic companies file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). That meant they only needed to show their version matched the brand in strength, dosage, and how the body absorbs it. No new safety data. No new trials. Just proof they’re the same. This cut development costs from $2.6 billion to $2-3 million per drug. Suddenly, dozens of companies could enter the market. And when more companies compete, prices drop.

Today, over 1,000 generic drugs get approved each year. In 2023 alone, the FDA approved 1,083. That’s not because the government is forcing prices down. It’s because the system makes it easy for new players to join the race.

Why Medicare’s New Price Negotiation Law Leaves Generics Out

In 2022, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act, which gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for some of the most expensive brand-name drugs. The first 10 drugs selected for negotiation include Ozempic, Wegovy, and Eliquis-all high-cost, single-source brands. Not one generic is on the list.

Why? Because the Department of Health and Human Services made it clear: generics already have competition. They don’t need negotiation. The CMS confirmed this in April 2024, stating the program targets only drugs with "no therapeutically equivalent generic or biosimilar alternatives." In other words, if there’s already a cheaper version on the shelf, Medicare doesn’t step in.

Studies back this up. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that applying international price benchmarks to generics would save Medicare just $2.1 billion a year-less than 0.4% of total generic spending. Meanwhile, negotiating prices on branded drugs could save $158 billion. That’s not a small difference. It’s why lawmakers focused where the biggest savings are.

How the FDA Keeps Generics Coming-Without Setting Prices

The FDA doesn’t set prices. But it does set the pace. The Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), renewed in 2022 with $750 million in industry fees, aims to cut approval times from 18 months to 10. That’s not just bureaucracy-it’s economic policy.

Faster approvals mean more competitors enter the market sooner. And more competitors mean faster price drops. In 2023, the FDA hit its goal: 92% of priority generic applications got a response within 10 months. That’s up from 60% in 2017. The result? A 35% increase in generic approvals since 2017.

But not all generics are equal. Some drugs are hard to copy-like inhalers, injectables, or creams with complex formulas. These "complex generics" take longer to approve. In 2024, only 38% of these met the 10-month target. To fix this, the FDA created a new submission template in late 2023. Early results show review times dropped 35% for pilot applications. That’s not price control. That’s removing roadblocks so competition can do its job.

The Real Threat to Generic Prices: Anti-Competitive Tactics

Even in a competitive market, bad actors can mess things up. One of the biggest threats? "Pay-for-delay" deals. That’s when a brand-name company pays a generic manufacturer to delay launching its cheaper version. It’s not a legal gray area-it’s illegal. The FTC has been chasing these deals for years.

In 2023 alone, the FTC challenged 37 pay-for-delay agreements. They estimate that stopping these deals saves consumers $3.5 billion a year. The FTC also blocked the Teva-Sandoz merger in January 2024 because it would have reduced competition for 13 generic drugs. That’s not price setting. That’s antitrust enforcement.

Another tactic? "Product hopping." That’s when a brand company slightly changes its drug-say, switching from a pill to a capsule-and pushes doctors to prescribe the new version. Then they stop making the old one. This shuts out generics that were already approved for the original version. The FDA’s 2024-2026 plan now targets this practice head-on, especially for high-revenue drugs.

What About Price Spikes? Are Generics Ever Unaffordable?

Yes-sometimes. But not often. And when they do spike, it’s usually because of supply issues, not greed.

In 2023, the FDA reported only 0.3% of generic drugs had price increases over 100% in a single year. Most spikes happen because a manufacturer shuts down production. Maybe the price got too low to cover costs. Maybe the factory failed inspection. Maybe the raw materials got too expensive. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists found that 18% of hospital pharmacists faced shortages of critical generics because prices fell below production costs. That’s a broken incentive, not a price control problem.

One Reddit user complained their generic sertraline jumped from $4 to $45. That made headlines. But it was an outlier. The KFF Consumer Survey in 2024 found 76% of Medicare Part D users pay $10 or less for generics. And 82% of generic users say they’re satisfied with affordability-compared to just 41% of brand-name users.

So yes, price spikes happen. But they’re rare, localized, and usually tied to supply chain issues-not market manipulation. Fixing those requires better oversight of manufacturing, not price ceilings.

Why Experts Say Price Controls Would Hurt More Than Help

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor at Harvard Medical School, told the Senate Finance Committee in 2024: "Generic drugs have demonstrated the ability to achieve substantial price reductions through competition alone, making additional price controls unnecessary and potentially counterproductive."

He’s not alone. The Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy says government price regulation could discourage new manufacturers from entering the market. If you cap prices too low, companies won’t make drugs that barely turn a profit. And if they stop making them, shortages follow.

The Congressional Research Service added in June 2025 that direct price regulation of generics would likely face "significant legal challenges" because current law doesn’t give Medicare the authority to set prices for these drugs. Even if it did, the savings would be tiny compared to the risk of fewer generics on the shelf.

The real solution? More competition. Faster approvals. Stronger enforcement against anti-competitive behavior. That’s what the FDA, FTC, and CMS are doing. And it’s working.

The Bigger Picture: Why the U.S. Has the Cheapest Generics in the World

The U.S. has 14.7 generic manufacturers per drug on average. Europe has 8.2. Japan has 5.3. That’s why U.S. generic prices are lower than almost any other developed country-by volume, we consume 42% of the world’s generics, but only pay 29% of the global value.

That’s not luck. It’s policy. The U.S. didn’t create a price control system. It created a competition system. And it’s the most effective one in the world.

By 2030, the Congressional Budget Office predicts generic prices will keep falling at 3.5% per year-just from market forces. Branded drug prices? They’ll rise 0.8%. The difference isn’t magic. It’s structure.

What You Can Do: How to Save More on Generics

- Ask your pharmacist if there’s a generic version-even if your doctor didn’t prescribe one.

- Use mail-order pharmacies or bulk-buy programs through Medicare Part D. Many generics cost less than $10 for a 90-day supply.

- Check the FDA’s Generic Drug User Fee Public Dashboard. It shows which generics are coming soon. If a new one’s approved, prices will drop in weeks.

- If your generic price suddenly jumps, ask if it’s the same manufacturer. If not, switch. Price spikes often happen when one company dominates a market.

Why doesn’t Medicare negotiate prices for generic drugs?

Medicare doesn’t negotiate prices for generic drugs because they already have strong market competition. When multiple manufacturers sell the same generic, prices drop naturally-often to 10-15% of the original brand’s cost. The government’s drug negotiation program is designed for brand-name drugs with no generic alternatives, where competition is absent. Adding generics to the program would save very little-just $1.2 billion annually-while risking unintended consequences like reduced supply.

Are generic drugs always cheaper than brand-name drugs?

Yes-almost always. After a brand-name drug’s patent expires, generic versions typically cost 80-85% less. Even when only one generic is available, prices are usually 75% lower. With three or more generics, prices often fall to just 10-15% of the brand’s original price. The only exceptions are rare cases where a single manufacturer controls the entire market, or when supply chain issues cause shortages.

Can a generic drug be more expensive than the brand?

Technically yes, but it’s extremely rare and usually temporary. Sometimes, if a brand-name drug is sold at a deep discount through coupons or rebates, its out-of-pocket cost might appear lower than a generic. But that’s a pricing trick, not true cost. The actual wholesale price of the generic is still far lower. In rare cases, a shortage of a generic can cause a temporary spike-but these are exceptions, not the rule.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

A generic is an exact copy of a traditional chemical drug, like metformin or lisinopril. A biosimilar is a close copy of a biologic drug-like insulin or Humira-which is made from living cells and is much more complex to replicate. Biosimilars are not called generics because they can’t be perfectly identical. They’re approved under different rules and are often more expensive than traditional generics, though still cheaper than the original biologic.

Why do some generic drugs disappear from shelves?

Generic drugs disappear when manufacturers can’t make a profit at the current price. If the price drops too low-often due to too many competitors-the company may shut down production. This is especially common with older, low-margin drugs. The FDA and FTC are working to prevent this by cracking down on anti-competitive behavior and encouraging new manufacturers to enter the market, but it’s a delicate balance between low prices and sustainable production.

If you’re paying more than $10 for a common generic, check your pharmacy’s cash price. Often, it’s lower than your insurance copay. And if you see a sudden price jump, ask if a new manufacturer just entered the market-it might mean prices will drop again soon.

The Do's and Don'ts of Teething Pain Relief for Your Baby

The Do's and Don'ts of Teething Pain Relief for Your Baby

Feverfew and Anticoagulants: What You Need to Know About Bleeding Risk

Feverfew and Anticoagulants: What You Need to Know About Bleeding Risk

Top 6 Alternatives to GoodRx for Prescription Savings

Top 6 Alternatives to GoodRx for Prescription Savings

How to Access FDA Adverse Event Databases for Safety Monitoring

How to Access FDA Adverse Event Databases for Safety Monitoring

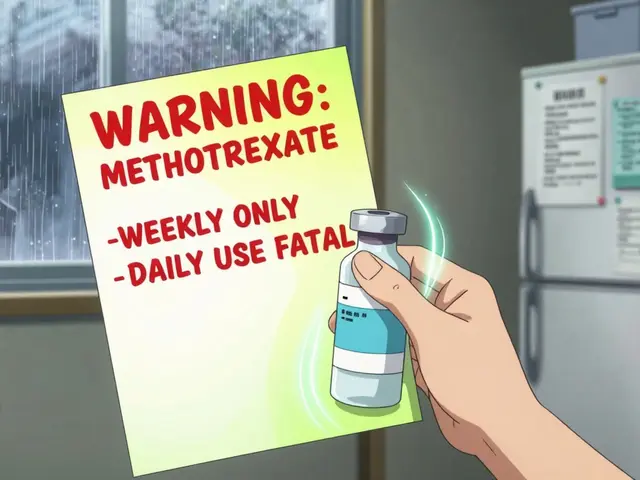

How to Document Safety Alerts on Your Medication List for Better Patient Safety

How to Document Safety Alerts on Your Medication List for Better Patient Safety

Chelsea Moore

December 2, 2025 AT 02:04Doug Hawk

December 2, 2025 AT 12:06John Morrow

December 4, 2025 AT 02:36Kristen Yates

December 5, 2025 AT 02:23Saurabh Tiwari

December 6, 2025 AT 06:44Michael Campbell

December 7, 2025 AT 01:26Victoria Graci

December 8, 2025 AT 00:00Saravanan Sathyanandha

December 9, 2025 AT 20:19Fern Marder

December 10, 2025 AT 17:52Carolyn Woodard

December 11, 2025 AT 06:22Michael Campbell

December 13, 2025 AT 05:55