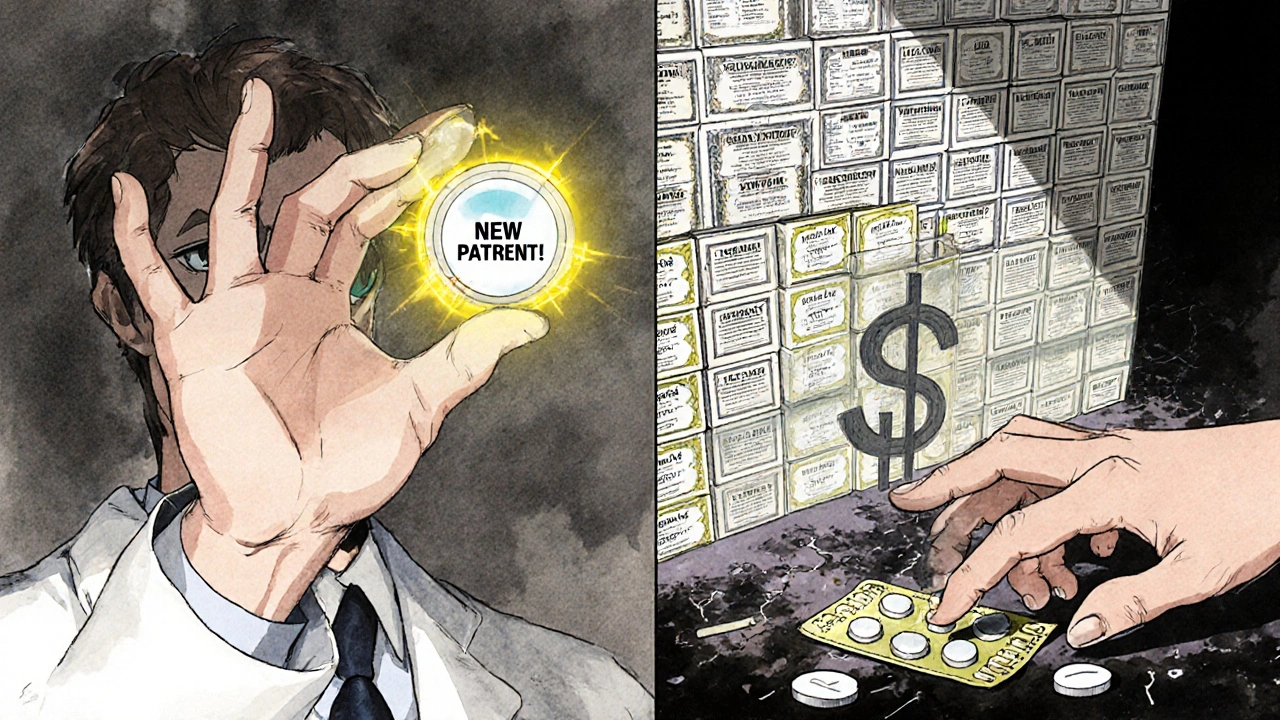

When a blockbuster drug’s patent is about to expire, the company doesn’t just sit back and wait for cheaper generics to flood the market. Instead, they often launch a quiet, legal campaign to keep their monopoly alive - sometimes for decades longer than intended. This isn’t innovation. It’s evergreening.

What Evergreening Really Means

Evergreening is when drugmakers file new patents on tiny changes to an existing medicine - not to make it better for patients, but to delay competitors. These aren’t breakthroughs. They’re tweaks: a new pill coating, a slightly different dosage, a slow-release version, or a combo with another drug that’s already off-patent. The goal? Keep the original drug off the shelves and block generics from entering. The U.S. patent system gives inventors 20 years of protection from the date they file. But with evergreening, companies stack on extra layers of exclusivity. A drug might get five years for being new, three more for new clinical trials, six months for pediatric testing, or seven for being labeled an orphan drug. Add them up, and a drug originally approved in 2005 might still have patent protection in 2035 - even if the core molecule hasn’t changed. Take AstraZeneca’s Prilosec, a heartburn drug. When its patent neared expiration, they rolled out Nexium - essentially the same active ingredient, just in a slightly different form. Nexium wasn’t more effective. But it came with a new patent, a new brand, and a new price tag. Patients paid more. Generics stayed off the market. And AstraZeneca extended its monopoly on that drug family by more than 90 years across just six products.How It Works: The Playbook

Pharmaceutical companies don’t wing this. They have teams dedicated to lifecycle management - lawyers, chemists, and regulatory experts who start planning five to seven years before a patent expires. Here’s how they do it:- Product hopping: Replace the old drug with a new version - often with no real clinical benefit - and stop producing the original. This forces patients and doctors to switch, making generics less attractive.

- Patent thickets: File dozens, even hundreds, of patents around one drug. AbbVie filed 247 patents on Humira, an autoimmune drug. Even if one patent gets knocked down, 246 others remain. Generic makers can’t afford to fight them all.

- Authorized generics: The brand company launches its own generic version at a lower price. It looks like competition, but it’s still their product. This keeps the market under their control and scares off real generics.

- OTC-switching: Move the drug from prescription to over-the-counter status. This creates a new patent window and keeps the brand alive even as the prescription version faces generic competition.

- Pharmacogenomics: Patent a genetic test that predicts who responds to the drug. Now, only patients who pass the test can legally get the branded version - effectively locking out generics for those who need it most.

Why It’s a Problem

Generic drugs are cheaper because they don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials. They prove they’re the same as the original. That’s why prices drop 80-85% within a year of generic entry. But evergreening blocks that. When generics can’t enter, prices stay high. Humira, for example, cost patients an average of $70,000 per year before generics finally arrived in 2023 - after 20 years of patent extensions. AbbVie made over $200 billion from it. That’s $40 million a day in revenue, all thanks to a patent strategy that had little to do with medical progress. Patients suffer. So do insurers, Medicare, and state health programs. In 2023, the U.S. spent over $1.4 trillion on prescription drugs. A significant chunk of that went to drugs protected by evergreening - not because they were better, but because no one else could sell them. And it’s not just the U.S. The World Health Organization called evergreening a barrier to affordable medicines in low- and middle-income countries. When a life-saving drug stays expensive for 20 extra years, people die waiting.

Is It Legal? Yes. Is It Right?

The courts have mostly let it slide. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office approves these patents because, technically, they meet the legal definition of “novelty.” A new coating? New patent. A new dosage form? New patent. Even if the change adds zero benefit. Critics call it gaming the system. Robin Feldman, a law professor at UC Hastings, found that 78% of new patents on prescription drugs were for existing drugs - not new ones. That’s not innovation. That’s financial engineering. Some companies argue that evergreening funds future research. But the math doesn’t add up. Developing a new drug costs $2.6 billion and takes over a decade. Evergreening costs a fraction of that - often under $100 million - and delivers the same profits. It’s not an incentive. It’s a shortcut.What’s Changing?

Pressure is building. In 2022, the Federal Trade Commission sued AbbVie over Humira’s patent thicket, calling it an anticompetitive scheme. The Inflation Reduction Act gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for the most expensive drugs - a direct hit to evergreening’s profit model. The European Medicines Agency now requires companies to prove a “significant clinical benefit” before granting extra exclusivity. That’s a big deal. It forces them to show real improvement, not just a new pill shape. And now, generic manufacturers are fighting back. They’re pooling resources to challenge patent thickets. In 2023, the first Humira biosimilars finally hit the U.S. market - not because the patents were perfect, but because enough lawsuits piled up to make it worth the risk.

What You Can Do

If you’re on a branded drug that’s about to go generic, ask your doctor or pharmacist: Is there a generic version available? Is this new version really better, or just newer? If you’re on Medicare or have employer insurance, ask your plan about preferred drugs. Many plans now push for generics or biosimilars - especially when they’re proven to be just as effective. And if you’re frustrated by high drug prices, speak up. Patient advocacy groups are pushing for patent reform. Your voice adds weight to the call for change.What Comes Next?

The next wave of evergreening is already here. Companies are moving from pills to biologics - complex drugs made from living cells. These are harder to copy. So instead of filing patents on new formulations, they’re patenting delivery systems, storage methods, and even how the drug is administered. Nanotechnology is another frontier. Tiny drug particles that change how the body absorbs the medicine? New patent. Genetic tests to predict who responds? New patent. The goal remains the same: keep the money flowing. But the tools are getting more sophisticated. And so are the legal battles. The system was designed to reward innovation. But when the reward is given for the smallest tweak, it stops working for patients. The question isn’t whether evergreening is legal. It’s whether we’re okay with a system that lets corporations profit from delay - while people wait, and pay, and suffer.Is evergreening illegal?

No, evergreening is not illegal in the U.S. or most countries. It’s a legal strategy that exploits loopholes in patent law. Companies file patents on minor changes - like a new coating, dosage form, or combination - and regulators approve them if they meet basic novelty requirements. The problem isn’t legality; it’s whether these changes offer real medical value. Most don’t.

How long can a drug stay protected through evergreening?

There’s no fixed limit. A drug’s original patent lasts 20 years from filing. But with additional exclusivity periods - like three years for new clinical trials, six months for pediatric studies, or seven for orphan drug status - total protection can stretch to 30 years or more. AstraZeneca extended protection on some drugs by over 90 years across multiple patents. AbbVie’s Humira was protected for nearly 20 years before generics arrived.

Do evergreened drugs work better than generics?

Almost always, no. Studies show that most evergreened versions - like Nexium after Prilosec or new Humira formulations - have no meaningful clinical advantage. They’re chemically identical or nearly so. The difference is price. Generics are 80-85% cheaper because they don’t repeat costly trials. If a new version doesn’t improve outcomes, it’s not innovation - it’s marketing.

Why don’t generic companies challenge these patents more often?

Because it’s expensive and risky. Big pharma files dozens of patents - sometimes over 200 - on a single drug. Challenging one patent costs millions. Challenging 50? It’s financially impossible for most generics. This is called a “patent thicket.” Even if the patents are weak, the cost of fighting them deters competition. Only when enough lawsuits pile up, or when regulators step in, do generics succeed.

Are there any drugs that have successfully avoided evergreening?

Yes. Drugs with simple, well-defined molecules - like metformin for diabetes or simvastatin for cholesterol - have seen quick generic entry because they’re hard to tweak meaningfully. But these are the exceptions. Most high-revenue drugs today - especially biologics and complex formulations - are protected by thick patent networks. Evergreening is the rule, not the exception, for blockbuster medications.

Nebulizers vs. Inhalers: Which One Really Works Better for Asthma and COPD?

Nebulizers vs. Inhalers: Which One Really Works Better for Asthma and COPD?

The Impact of Seasonal Changes on Vitamin D Levels

The Impact of Seasonal Changes on Vitamin D Levels

Ischemia and Sleep Apnea: Risks, Symptoms, Tests, and Treatment (2025 Guide)

Ischemia and Sleep Apnea: Risks, Symptoms, Tests, and Treatment (2025 Guide)

Military Deployment and Medication Safety: How Heat, Storage, and Access Impact Soldier Health

Military Deployment and Medication Safety: How Heat, Storage, and Access Impact Soldier Health

How to Buy Cheap Generic Metformin Online Safely

How to Buy Cheap Generic Metformin Online Safely

Gabe Solack

November 18, 2025 AT 23:58Man, I had no idea this was so systematic. I just thought drug prices were crazy because of greed, but this level of legal engineering? 😳 I switched from brand to generic for my blood pressure med last year and saved $400/month. Still can’t believe how much we’re overpaying just because some lawyer figured out how to patent a different pill shape.

Yash Nair

November 19, 2025 AT 17:57USA always cheating the world with patents lol. India makes cheap lifesaving drugs for millions but US pharma sue us for 'stealing' their IP. Pathetic. Your system is broken and you people still act like victims. Go cry to your congressmen while your grandma skips her meds.

Bailey Sheppard

November 20, 2025 AT 01:19This is such an important topic and you laid it out so clearly. I’ve been on Humira for years and honestly didn’t realize how much of the price was just patent games. It’s frustrating but also kind of hopeful that generics are finally starting to break through. Maybe we’re turning a corner.

Girish Pai

November 21, 2025 AT 22:27Patent thickets are a classic case of regulatory arbitrage - pharma firms exploit the asymmetric cost structure between litigation and R&D. The Hatch-Waxman Act was predicated on a static equilibrium model, but the industry evolved into a dynamic rent-extraction ecosystem. The FDA’s ‘significant clinical benefit’ threshold in the EU is a step toward structural correction, but without price caps, it’s still just a band-aid.

Kristi Joy

November 23, 2025 AT 12:34For anyone reading this and feeling overwhelmed - you’re not alone. Talking to your pharmacist about generics is one of the most powerful things you can do. And if you’re on Medicare, ask about preferred drug lists. Small actions add up. We’ve got this.

Katelyn Sykes

November 25, 2025 AT 02:15They’re patenting how the drug is delivered now like next gen evergreening is gonna be nano-particles and genetic tests so only rich people get the real meds 😭

Hal Nicholas

November 26, 2025 AT 22:06Of course they’re doing this. The entire system is rigged. Big Pharma owns Congress, the FDA, and half the doctors. This isn’t capitalism - it’s feudalism with IV drips. And don’t even get me started on how they bribe insurers to push brand names. You think this is about health? It’s about control.

Louie Amour

November 27, 2025 AT 23:54Wow, so the real crime isn’t the drugs being expensive - it’s that people actually believe this is normal. If you’re still taking brand-name meds without asking if there’s a generic, you’re complicit. This isn’t rocket science. It’s basic consumer awareness. Get educated or get priced out.

Kristina Williams

November 28, 2025 AT 19:42They’re putting microchips in the pills to track you. That’s why they won’t let generics in - they need to monitor your biometrics. The same companies that make the drugs also run the insurance. You think it’s coincidence? Wake up.

Shilpi Tiwari

November 29, 2025 AT 06:57The biologics space is the next frontier - complex molecules, high barriers to entry, and patent strategies targeting delivery mechanisms and formulation stability. The regulatory pathway for biosimilars is still nascent in many jurisdictions, and the cost of analytical comparability studies remains prohibitive. This isn’t just evergreening - it’s patent architecture designed to lock in monopolies for 25+ years.