When you pick up a prescription for generic metformin or amoxicillin, you probably don’t think about who moved it from the factory to your pharmacy. But behind that $4 bottle of pills is a complex, high-stakes economic system that makes more money on generics than on brand-name drugs-despite generics costing far less to make. This isn’t just about supply chains. It’s about who gets paid, how much, and why the system works the way it does.

The Three-Tier System No One Talks About

The U.S. generic drug distribution system runs on a three-tier model: manufacturers, wholesalers, and pharmacies. It’s been this way since the Prescription Drug Marketing Act of 1987, but most people don’t realize how much power sits in the middle-with the wholesalers. Three companies-AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson-control about 85% of the entire market. That’s not competition. That’s a cartel with a legal license to move pills. These wholesalers don’t just store drugs. They decide which manufacturers get shelf space, how much pharmacies pay, and when shortages happen. They’re the gatekeepers. And here’s the twist: they make more profit on generic drugs than on branded ones-even though generics make up only about 9% of total drug revenue.Why Generics Are a Gold Mine for Wholesalers

In 2009, generic drugs generated $1.7 billion more in gross profits for the Big Three wholesalers than brand-name drugs did. That’s not a typo. Generics brought in less money overall, but they were far more profitable per unit. Wholesalers made eleven times more profit on each dollar spent on generics compared to branded drugs-$32 versus $3 per unit. Pharmacies made nearly the same: $32 on generics, $3 on brands. How? Because manufacturers of generics are desperate to win contracts. With hundreds of companies making the same generic drug, they slash prices to get into the system. Wholesalers, with their monopoly-like control, can demand deeper discounts. Then they mark it up just enough to make huge margins on volume. It’s not about the price tag-it’s about the squeeze. Meanwhile, brand-name manufacturers still enjoy gross margins of 76.3%. But they’re fighting for market share in a crowded field. Generic makers? They’re fighting for survival. And the wholesalers? They’re sitting in the middle, collecting the difference.

How Pricing Actually Works

Wholesalers don’t just slap on a markup. They use four pricing strategies, and one dominates: tiered pricing.- Cost-plus pricing: Add a fixed percentage to production cost. Simple, but ignores market pressure.

- Market-based pricing: Match what competitors charge. Safe, but cuts into margins.

- Value-based pricing: Charge based on perceived need. Rare in generics-no one’s paying more for the same pill.

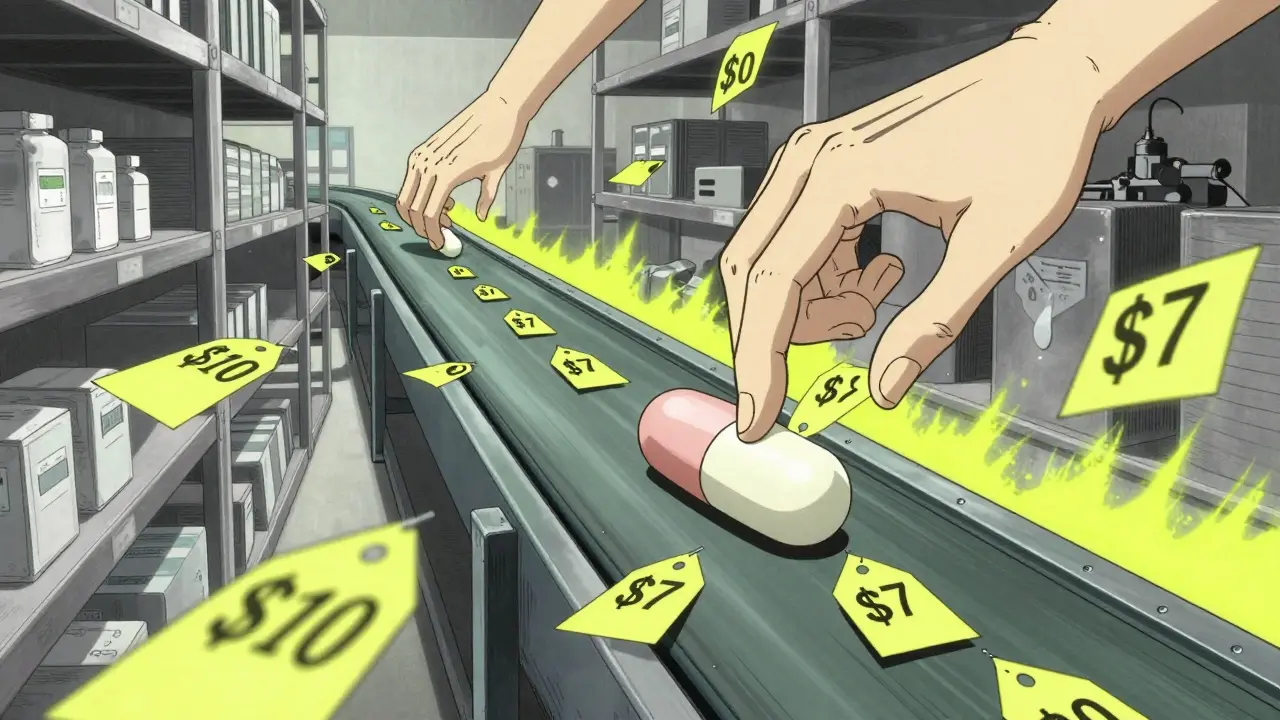

- Tiered pricing: The real game-changer.

- Under 100 units: $10 per pill

- 100-500 units: $8 per pill

- Over 500 units: $7 per pill

Why Generic Prices Keep Changing

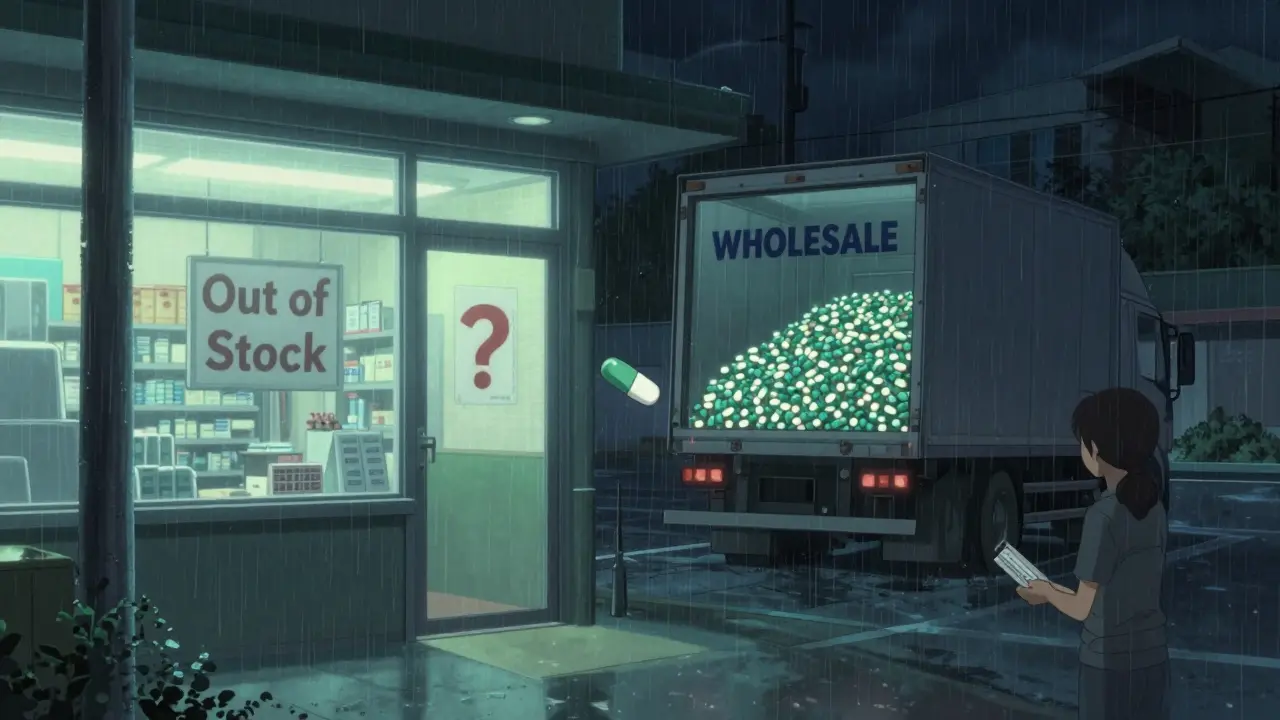

Generic drug prices aren’t stable. They swing like a pendulum. Between 2021 and 2022, prices fell. That was the deflationary cycle-too many makers, too little demand, too much competition. But in 2023, things flipped. Shortages hit. A single plant shutdown in India or China can knock out 40% of the U.S. supply of a common antibiotic. Suddenly, demand spikes. Wholesalers raise prices. Pharmacies scramble. Patients pay more. This isn’t an accident. It’s a feature of the system. Wholesalers benefit from volatility. When a drug is scarce, they can charge more. When it’s plentiful, they buy low and hold. They don’t care if you get your meds on time. They care about their balance sheet. The Commonwealth Fund found that wholesalers influence shortages in four ways: setting prices, manipulating list prices, competing for specialty drugs, and controlling supply flow. That last one is the most dangerous. If a wholesaler decides a drug isn’t profitable enough to stock, it disappears. No warning. No explanation. Just gone.

Who Wins and Who Loses

Let’s break it down:- Manufacturers: Make less on generics than brands-$18 gross profit per unit vs. $58. But they still need to produce enough to stay in business.

- Wholesalers: Make 11x more on generics than brands. Net margins? Only 0.5%. But with billions in volume, that’s billions in profit.

- Pharmacies: Make 12x more on generics. Independent pharmacies rely on these margins to survive.

- Patients: Pay more than they should. The system doesn’t reward efficiency. It rewards control.

What Could Change

There are signs the system is cracking. Regulators are starting to pay attention. The Commonwealth Fund says policymakers need to understand how wholesalers drive prices and shortages. Some states are exploring direct manufacturer-to-pharmacy distribution to cut out the middleman. Others are forcing transparency in pricing. But change moves slowly. The Big Three spend millions lobbying. They own the infrastructure. They control the data. And as long as pharmacies need them to get pills, they’ll keep paying the price. The only real solution? More competition. More transparency. And maybe, someday, a system where the cheapest drugs don’t become the most profitable-and the people who need them don’t pay the cost.Why are generic drugs cheaper to make but more profitable to sell?

Generic drugs cost less to produce because multiple manufacturers make the same formula after patents expire. But wholesalers make more profit on them because manufacturers compete so hard for contracts that they slash prices. Wholesalers then mark them up just enough to earn high margins on high volume-sometimes eleven times more profit per dollar than on brand-name drugs.

Who controls the generic drug supply in the U.S.?

Three companies-AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson-control about 85% of the U.S. pharmaceutical wholesale market. They decide which drugs get distributed, how much pharmacies pay, and when shortages occur. Their size gives them immense power over pricing and availability.

How do wholesalers make money if their net margins are so low?

Wholesalers have net margins as low as 0.5%, but they move billions in volume. A tiny margin on massive sales adds up. For example, if they distribute $10 billion in generic drugs with a 0.5% net margin, that’s $50 million in profit. They also use tiered pricing and bulk orders to lock in volume and reduce inventory costs.

Why do generic drug prices go up during shortages?

When a manufacturer shuts down or faces delays, supply drops. Wholesalers still have inventory, so they raise prices. Pharmacies have no choice but to pay more-or risk running out. This creates inflation in specific drugs, even as overall generic prices trend downward. Shortages are often predictable, but wholesalers rarely warn customers in advance.

Can pharmacies buy directly from manufacturers to avoid wholesalers?

Some can, but it’s rare. Most pharmacies don’t have the infrastructure to handle logistics, storage, or regulatory compliance. A few states are testing direct distribution models to cut out wholesalers, but the Big Three still control the national network. Until that changes, most pharmacies rely on them-even if it costs more.

Female Cialis (Tadalafil) vs. Alternatives: Pros, Cons & Best Choices

Female Cialis (Tadalafil) vs. Alternatives: Pros, Cons & Best Choices

Drug Withdrawals and Recalls: Why Medications Get Removed from the Market

Drug Withdrawals and Recalls: Why Medications Get Removed from the Market

How to Check for Drug Interactions Before Starting New Medications: A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Check for Drug Interactions Before Starting New Medications: A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Involve Family or Caregivers in Medication Support

How to Involve Family or Caregivers in Medication Support

John O'Brien

January 27, 2026 AT 10:23These three giants are basically drug cartels with office chairs and W-2s. I got my metformin for $4 but the wholesaler made $32 off it. That’s not capitalism, that’s theft with a balance sheet.

Paul Taylor

January 28, 2026 AT 18:09Let me tell you something about how this system actually works the way it does because i’ve seen it from the inside when i worked in supply chain for a midsize pharmacy chain and let me say this the tiered pricing model is designed to trap you not help you they want you to buy in bulk so they can lock your cash flow and then when a shortage hits they hold back inventory like it’s a video game and you’re the noob player who doesn’t know when to reload

and dont even get me started on how a single factory in india can knock out 40 percent of the supply of amoxicillin and nobody tells you until you’re standing in the pharmacy with your kid coughing and the shelf is empty

the whole thing is a rigged game where the middlemen get rich off the desperation of people who just need their pills and the manufacturers are so desperate to survive they’ll sell at a loss just to stay in the game

pharmacies are caught in the middle too they make more on generics but they’re forced to order way more than they can sell just to get the discount and then they’re stuck with expired inventory and no one cares

the real tragedy is that this isn’t some hidden secret its all public data if you know where to look but nobody talks about it because the lobbyists pay off the regulators and the media is too busy covering celebrity breakups

we need direct manufacturer to pharmacy distribution and we need it now because this system is not just broken its actively cruel

and dont even get me started on how the big three own the data so they know exactly when to raise prices and when to pretend they’re out of stock

its like they’re playing monopoly with our medicine

and yeah i know i went long but this is literally life or death for millions of people and we’re treating it like a stock market joke

Desaundrea Morton-Pusey

January 29, 2026 AT 12:10America’s biggest export is now pharmaceutical extortion. Who knew we’d become the world’s pharmacy mafia?

Murphy Game

January 31, 2026 AT 04:11Notice how no one mentions the Fed’s role in enabling this? The whole system is backed by shadow banking and offshore shell companies. The Big Three aren’t just wholesalers-they’re fronts for a global asset-stripping operation. You think this is about pills? It’s about control. They’re testing the limits of how much power one sector can hoard before the public wakes up. And they’re winning.

Kegan Powell

February 1, 2026 AT 13:00bro this is wild but also kinda beautiful in a messed up way 😅 like imagine if we treated food distribution like this imagine if you had to buy 500 lbs of rice just to get the discount and then the supplier decided to 'run out' for a month just to jack up prices 🤯

we need to rebuild this from the ground up with transparency and community co-ops maybe even blockchain for tracking supply chains

the fact that people are dying because a wholesaler decided a drug wasn't profitable enough to stock… that’s not a market failure that’s a moral collapse

we can do better than this

Harry Henderson

February 2, 2026 AT 23:25Enough is enough. We need to break up these wholesalers like we did with Big Tobacco. This isn’t healthcare-it’s a racket. Time to drag these CEOs into Congress and make them explain why their net margin is 0.5% but they’re still billionaires.

suhail ahmed

February 3, 2026 AT 19:07in india we have a different system-direct supply from manufacturers to pharmacies with state-level bulk purchasing. no middlemen. no tiered traps. no shortages because of greed. our insulin costs 10 cents because we cut out the sharks. america could do this if it wanted to. but it chooses not to because the profit is too good for the few.

Candice Hartley

February 5, 2026 AT 06:42My dad missed his blood pressure meds last month because the wholesaler 'ran out.' He’s fine now but… this shouldn’t happen. 😔

Andrew Clausen

February 6, 2026 AT 15:59The claim that wholesalers make 11x more profit per dollar on generics than on branded drugs is mathematically inconsistent with the stated gross profit figures. The data presented conflates gross profit with net margin. Without accounting for overhead, logistics, and regulatory compliance costs, the conclusion is misleading. The real issue is lack of price transparency-not monopolistic behavior per se.

Anjula Jyala

February 7, 2026 AT 18:01tiered pricing is just a fancy word for predatory volume exploitation the real issue is the lack of antitrust enforcement under the Sherman Act the big three are operating as a classic oligopoly with vertical integration and information asymmetry the FDA should be mandating real-time inventory disclosures and price ceilings on essential generics no excuses

Kathy McDaniel

February 9, 2026 AT 09:29i just read this and cried a little. my mom takes 7 meds and i swear half the time they’re out of stock. why does it have to be so hard to just get your pills?

April Williams

February 11, 2026 AT 06:11They’re not just profiting-they’re weaponizing medicine. This is how you control a population. Make them dependent on pills, then make the pills unreliable. Watch them beg. Watch them pay. Watch them stay silent. This isn’t capitalism. This is fascism with a pharmacy logo.

astrid cook

February 12, 2026 AT 14:05Everyone’s mad at the wholesalers but what about the pharmacies? They’re the ones charging patients $40 for a $4 pill. They’re complicit. Why don’t we blame them too? They know what’s going on.

Kirstin Santiago

February 12, 2026 AT 17:28Thank you for writing this. I’ve been trying to explain this to my friends for years and no one gets it until they read something like this. The fact that generics are the most profitable part of the system is so counterintuitive-but makes total sense once you see the mechanics. We need more people talking about this.