Drug Withdrawal Timeline Calculator

How Long Will It Take For This Drug to Be Withdrawn?

Calculate estimated withdrawal timeline based on FDA approval type and year of approval using data from recent studies.

Every year, dozens of medications disappear from pharmacy shelves-not because they’re outdated, but because they’re dangerous or don’t work. This isn’t a glitch in the system. It’s the system working as it should. But for years, it worked too slowly. Patients kept taking drugs that were later proven ineffective. Doctors kept prescribing them. And the FDA, the agency meant to protect public health, often took years to act.

How a Drug Gets Approved-And Why It Might Get Taken Down

The FDA doesn’t approve drugs because they’re perfect. It approves them because, based on the data available, the benefits outweigh the risks. That’s the standard. But that standard changes once a drug hits the market. Real-world use reveals things clinical trials can’t catch: rare side effects, long-term harm, or simply that the drug doesn’t deliver what it promised.

Most drugs get traditional approval after years of testing. But for serious conditions like cancer or ALS, the FDA sometimes uses accelerated approval. This lets drugs reach patients faster-based on early signs of benefit, like tumor shrinkage, rather than proof that patients live longer or feel better. It’s a lifeline for people with few options. But it’s also a gamble. About 40% of all accelerated approvals are for cancer drugs. And of those, nearly one in four eventually gets pulled.

The problem? The FDA used to wait years to act. Take Makena, a drug approved in 2011 to prevent preterm birth. In 2020, a large study showed it didn’t work. But the FDA didn’t pull it until 2022. Over 150,000 women took it during that gap. That’s not an outlier. Between 2010 and 2020, 12.7% of accelerated approval drugs were withdrawn. Patients were exposed for an average of over four years before the FDA stepped in.

The New Rules: What Changed in 2023

In December 2023, the FDA got a major upgrade. The Consolidated Appropriations Act gave it real power to act fast. Before, the agency could only ask sponsors to withdraw a drug. Now, it can force it. And it has clear, enforceable steps.

The law says the FDA can move quickly if:

- The company doesn’t do the required follow-up studies

- Those studies prove the drug doesn’t work

- Other data-like real-world patient records-show it’s unsafe or useless

- The company lies about the drug’s benefits in its marketing

There’s a timeline now. The FDA gives the company 30 days to respond. A meeting must happen within 60 days. A final decision comes within 180 days. That’s not perfect-but it’s a huge jump from the old average of 46 months.

The FDA even created a dedicated team: 12 scientists and doctors focused only on pulling bad drugs. Their goal? Cut withdrawal time from over four years to under one.

Voluntary vs. Mandatory: Who Pulls the Plug?

Not all withdrawals are forced. Sometimes, the company itself decides to pull the drug. That’s a voluntary withdrawal. It might happen because of low sales, manufacturing issues, or because they’ve found a better alternative.

But the FDA only considers a drug truly withdrawn from sale if the reason is safety or effectiveness. If a drug is out of stock for a few weeks because of a supply chain hiccup? That’s not a withdrawal. It’s a delay. The FDA’s 2018 guidance made this clear to avoid confusion.

Still, many companies wait until the FDA pushes them. Why? Because pulling a drug voluntarily looks better in the press. It sounds responsible. Forced withdrawal sounds like failure. And for a pharmaceutical company, reputation matters.

Who Gets Hurt When a Drug Lingers Too Long?

Patients are the ones who pay the price. Oncology patients are hit hardest. One study found that 26% of patients eligible for accelerated approval cancer drugs received treatments later withdrawn. In small cell lung cancer, that number jumped to 41%. These aren’t abstract stats. They’re real people.

One metastatic breast cancer patient wrote on a support forum in 2022: “I was on [withdrawn drug] for 18 months before the trial failed. My oncologist said it was standard of care. Now we know it didn’t help.”

Doctors are caught in the middle. They rely on FDA approval as a stamp of safety. When a drug is pulled, they scramble. Oncology practices report they have about 72 hours to switch patients to a new treatment. That’s not enough time to research alternatives, get insurance approval, or explain the change to a terrified patient.

Pharmacists struggle too. A 2022 survey found 63% still couldn’t tell if a drug in the Orange Book was withdrawn or just discontinued. The Orange Book is supposed to be the official list of approved drugs and their status. But if even professionals can’t read it, what chance does a patient have?

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Beyond the Lab

Drug withdrawals aren’t just about safety. They’re about trust. When patients find out they were given a drug that didn’t work, they lose faith in the system. Reddit threads like “How many of you have been on drugs later withdrawn?” have hundreds of comments. Most express fear-not just about the drug, but about the next one their doctor might prescribe.

It’s also a financial issue. Withdrawn drugs can cost billions. The FDA’s own audit found that only 42% of withdrawal notices included clear timelines for patient transitions. That means hospitals, insurers, and patients are left guessing-paying for treatments that offer no benefit.

And while the 2023 law is a step forward, it’s not a fix for everything. It only applies to drugs approved after the law passed. Drugs like Makena, approved in 2011, are still governed by the old, slow rules. That means more patients could still be exposed to ineffective treatments for years to come.

What’s Next? Real-World Data and Faster Decisions

The FDA is now testing real-world data to catch problems faster. A pilot program launched in early 2024 uses data from Flatiron Health, which tracks millions of cancer patients. Instead of waiting for a sponsor to run a five-year study, regulators can now see how patients are doing in real time. Did tumors grow? Did survival rates drop? Did side effects spike?

If this works, it could change everything. Instead of pulling drugs after years of delay, the FDA might act within months. That’s the goal.

But there’s a flip side. Some drug companies warn that faster withdrawals could scare off innovation. If a company knows it might be pulled after a single bad study, will it risk developing drugs for rare or hard-to-treat diseases? The FDA is trying to balance speed with fairness. Too fast, and you kill progress. Too slow, and you kill patients.

Right now, the system is in transition. The tools are better. The process is clearer. But the real test is still ahead: Will the FDA act the moment the evidence says to?”

What does it mean when a drug is withdrawn from the market?

When a drug is withdrawn, it means the manufacturer has stopped selling it, and the FDA has determined the reason is safety or effectiveness-not just a temporary shortage. The drug is no longer legally available for prescription or sale in the U.S. It’s removed from the FDA’s Orange Book, which means generic versions can no longer use it as a reference.

Can a drug be pulled even if it was FDA-approved?

Yes. FDA approval means the benefits outweigh the risks based on available data at the time. But once a drug is on the market, new evidence can emerge. If studies show it doesn’t work or causes unexpected harm, the FDA can and will withdraw it-even if it was once considered a breakthrough.

How long does it usually take for the FDA to withdraw a drug?

Before 2023, it took an average of 46 months-nearly four years-from the time a drug’s ineffectiveness was proven to the time it was pulled. The 2023 law aims to cut that to under 12 months for drugs approved after the law took effect. For older drugs, the old timeline still applies.

Are drug recalls the same as withdrawals?

No. A recall is usually about a specific batch or lot of a drug-maybe it’s contaminated or mislabeled. A withdrawal is about the entire drug being removed because it’s unsafe or ineffective. A recall can happen without withdrawal. A withdrawal almost always involves a recall of all distributed product.

How can I find out if a drug I’m taking has been withdrawn?

Check the FDA’s website for the most recent list of withdrawn drugs. You can also ask your pharmacist or doctor. The FDA publishes monthly updates to the Orange Book’s “Determination of Safety or Effectiveness” list. If your drug isn’t listed there, it’s still approved. But if you’re unsure, always verify with a trusted healthcare provider.

What to Do If Your Drug Gets Withdrawn

If you’re taking a drug that’s been pulled, don’t panic. But don’t ignore it either. Here’s what to do:

- Call your doctor immediately. Don’t stop the drug on your own-especially if it’s for a chronic condition like cancer or epilepsy.

- Ask for alternatives. Your doctor should have a plan ready. If they don’t, ask for a referral to a specialist.

- Check the FDA’s website. They post official notices with details on why the drug was pulled and what patients should do.

- Report any side effects. Even if the drug was withdrawn for lack of effectiveness, you may have experienced harm. Report it to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

- Keep records. Save prescriptions, doctor’s notes, and any communication about the withdrawal. This helps if you need to seek insurance coverage for a new treatment.

The system isn’t perfect. But it’s getting better. The 2023 reforms are the biggest change in decades. And for patients who’ve waited too long for justice, that’s something.

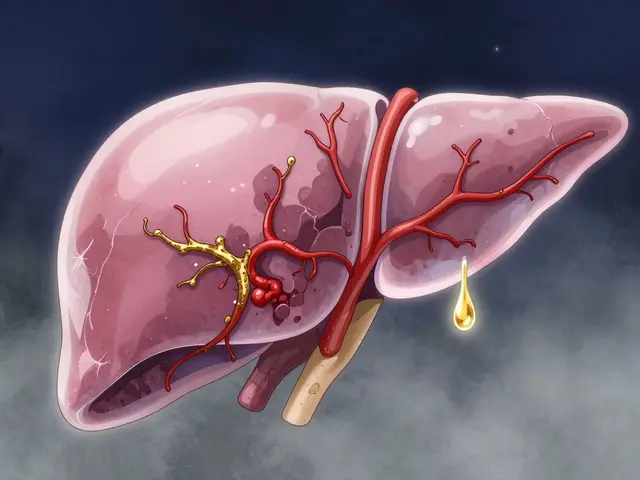

Cirrhosis: Understanding Liver Scarring, Failure Risk, and Transplant Options

Cirrhosis: Understanding Liver Scarring, Failure Risk, and Transplant Options

Discover Hericium Erinaceus: The All-Natural Miracle Supplement You Need to Try Today

Discover Hericium Erinaceus: The All-Natural Miracle Supplement You Need to Try Today

A Comprehensive Guide to Calcium Acetate Safety and Toxicity

A Comprehensive Guide to Calcium Acetate Safety and Toxicity

What Are Biosimilars? A Simple Guide for Patients

What Are Biosimilars? A Simple Guide for Patients

How to Choose OTC Eye Drops for Allergies, Dryness, and Redness

How to Choose OTC Eye Drops for Allergies, Dryness, and Redness

Alana Koerts

December 19, 2025 AT 10:40Drug withdrawals are just corporate PR theater. The FDA’s new rules look good on paper but they’re still playing catch-up. Companies knew this was coming and already buried the bad data in appendixes no one reads.

pascal pantel

December 19, 2025 AT 21:54Accelerated approval is a regulatory shell game. You’re trading long-term safety for short-term headlines. 40% of these approvals are oncology drugs? That’s not innovation-that’s desperation masquerading as science. And now they want to cut review time to 12 months? You’re not speeding up safety, you’re accelerating disaster.

Chris Clark

December 21, 2025 AT 21:39my buddy’s mom was on makena for 2 years before it got pulled. she had no idea. her doc just said ‘it’s standard.’ pharmacists don’t even know the orange book anymore. i mean, how is that even possible? we’re trusting our lives to systems that can’t keep their own records straight. and now they’re gonna fix it with a team of 12 people? lol. the whole thing is broken.

William Storrs

December 23, 2025 AT 03:44Hey, this is actually really good news. The FDA finally got a spine. It took decades, but they’re starting to protect patients instead of protecting profits. Yeah, it’s not perfect-but it’s a step. And steps matter. If you’re scared of change, you’re probably the same person who said ‘we can’t fix the system.’ Well, guess what? We’re fixing it. Slowly. But we’re fixing it.

James Stearns

December 25, 2025 AT 01:46One must acknowledge the profound epistemological rupture that has occurred within the pharmaceutical regulatory paradigm. The pre-2023 framework operated under a Hobbesian model of deferred accountability, wherein the state abdicated its duty to safeguard the citizenry in favor of corporate contractual immunity. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, while procedurally imperfect, constitutes a hermeneutic recalibration toward a Kantian imperative of public health sovereignty.

Guillaume VanderEst

December 26, 2025 AT 12:53Canada’s been doing this better for years. We don’t wait for 150k women to get pumped full of junk before we pull a drug. We use real-world data from day one. The FDA’s late to the party, but hey, better late than never, right?

Nina Stacey

December 28, 2025 AT 05:34i just want to say thank you for writing this i’ve been on so many meds that got pulled and no one ever told me why or what to do next and i felt so lost like i was just a number in some database and reading this made me feel seen and i know i’m not alone and that means a lot

Dominic Suyo

December 28, 2025 AT 13:28Let’s be real-the entire pharma-industrial complex is a Ponzi scheme built on placebo effects and FDA inertia. Accelerated approval? More like accelerated exploitation. And don’t get me started on the ‘voluntary’ withdrawals. That’s just corporate cowardice dressed in a suit. They’d rather let patients die than admit they sold snake oil.

Kevin Motta Top

December 30, 2025 AT 09:19Real-world data is the key. If we can track outcomes from EHRs and insurance claims in real time, we don’t need 5-year trials. We need sensors, not spreadsheets.

Alisa Silvia Bila

December 31, 2025 AT 13:54It’s scary how much we trust doctors to know what’s safe. But they’re just following the FDA’s stamp. If the stamp is wrong, we’re all just guessing. I hope this change sticks.

Sarah McQuillan

January 1, 2026 AT 16:46Wait, so you’re saying the FDA is now doing its job? That’s… actually kind of wild. I thought they were just a rubber stamp for Big Pharma. Maybe I’ve been wrong all along. Or maybe this is just PR. Either way, I’ll believe it when I see a drug pulled in 6 months, not 6 years.

Carolyn Benson

January 3, 2026 AT 14:47Every withdrawal is a mirror held up to society’s obsession with quick fixes. We want a pill for loneliness, for aging, for existential dread. We don’t want to change our lives-we want a chemical solution. And the system caters to that. The drug isn’t the problem. The hunger for easy answers is.

Chris porto

January 4, 2026 AT 23:52It’s not about speed. It’s about trust. If we can’t trust that a drug on the shelf is safe, then what do we trust? The doctor? The pharmacist? The label? We’re all just trying to survive in a system designed to profit from our fear.

Alana Koerts

January 5, 2026 AT 22:26And the 2023 law doesn’t even apply to drugs approved before then. So Makena? Still hanging around. The system’s still rigged.