When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, you’d expect generics to flood the market, lowering prices and giving patients more options. But in reality, many of these drugs stay expensive for years longer than they should. Why? Because patent litigation has become a strategic tool-not just to protect innovation, but to block competition.

How the System Was Supposed to Work

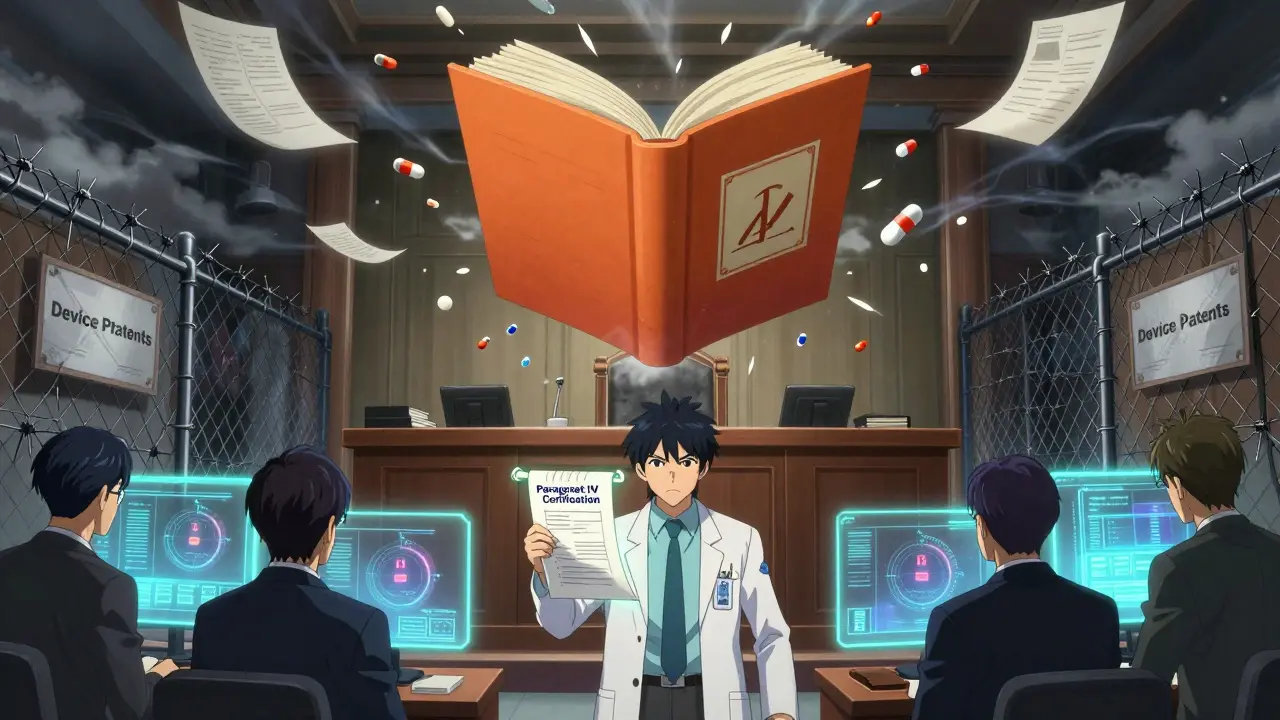

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 was designed to strike a balance. It gave brand-name drug companies extra patent time to make up for delays in FDA approval, while giving generic makers a faster, cheaper path to market through Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs). The key part? Paragraph IV certifications. When a generic company files one, it says: "This patent is invalid or won’t be infringed." That triggers a 30-month clock. During that time, the FDA can’t approve the generic-unless the court rules in the generic’s favor. This wasn’t meant to be a delay tactic. It was supposed to be a fair test: if the patent holds up, the generic waits. If it doesn’t, the market opens. But over time, the system got twisted.The Orange Book: A Legal Weapon in Disguise

The FDA’s Orange Book lists every patent tied to a brand-name drug. Only certain patents belong there: those covering the active ingredient, how it’s made, or how it’s used. But companies have found loopholes. They list patents for things like inhaler nozzles, packaging, or delivery devices-even when those aren’t part of the drug itself. In 2025, Judge Chesler ruled in Teva v. Amneal that six patents on a dose counter for ProAir® HFA didn’t qualify. The drug was albuterol sulfate inhalation aerosol. The counter? A device. Not the drug. That ruling was a big deal. Experts say it could invalidate 15-20% of all Orange Book listings right now. But the damage is already done. Brand companies have used this tactic for years. One drug, Eliquis (apixaban), has 67 patents. Semaglutide products (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus) have 152. Oncology drugs average 237. These aren’t just protections-they’re walls.Serial Litigation: The Delay Game

It’s not enough to file one lawsuit. Some brand companies play a game called serial litigation. They hold back patents, letting the first one expire, then file a new suit on a second patent. Then a third. And a fourth. The goal? Keep the 30-month stay going-over and over. The Association for Accessible Medicines found cases where generic entry was delayed by 7 to 10 years after the original patent expired. That’s not legal protection. That’s market control. And it’s expensive. The FTC estimates improper Orange Book listings delay generic competition for about 1,000 drugs every year, costing the system $13.9 billion annually.

Where Lawsuits Are Fought: The Eastern District of Texas

Not all courts are the same. In 2024, the Eastern District of Texas became the top venue for patent cases-38% of all filings. Why? It’s known for being fast, predictable, and favorable to patent holders. Even after the TC Heartland decision tried to limit forum shopping, big pharma companies moved back here. The District of Delaware and Western District of Texas trail behind at 15% and 22% respectively. Law firms like Fish & Richardson and Quinn Emanuel saw 35-40% revenue jumps in patent litigation in 2024. This isn’t just legal work-it’s a booming business.Settlements: Pay-for-Delay or Faster Access?

When a brand company sues a generic maker, they often settle. But these deals look suspicious. Sometimes, the brand pays the generic to stay off the market. That’s called a pay-for-delay settlement-and the FTC calls it illegal. But here’s the twist. A 2025 IQVIA report, commissioned by the same group that criticizes pay-for-delay, found that most settlements actually get generics to market faster-on average, more than five years before the patent expires. Why? Because without the chance to settle, generic companies won’t file Paragraph IV challenges at all. They’re scared of losing everything. So it’s not black and white. Some settlements are anti-competitive. Others are the only way generics can enter at all.

Fall Risk in Older Adults on Sedating Antihistamines: What You Need to Know and How to Stay Safe

Fall Risk in Older Adults on Sedating Antihistamines: What You Need to Know and How to Stay Safe

Healthcare System Communication: How Institutional Education Programs Improve Patient Outcomes

Healthcare System Communication: How Institutional Education Programs Improve Patient Outcomes

Buy Cialis Professional Online: Your Guide to Secure Purchase

Buy Cialis Professional Online: Your Guide to Secure Purchase

L-Tryptophan and Antidepressants: What You Need to Know About Serotonin Overlap and Risks

L-Tryptophan and Antidepressants: What You Need to Know About Serotonin Overlap and Risks

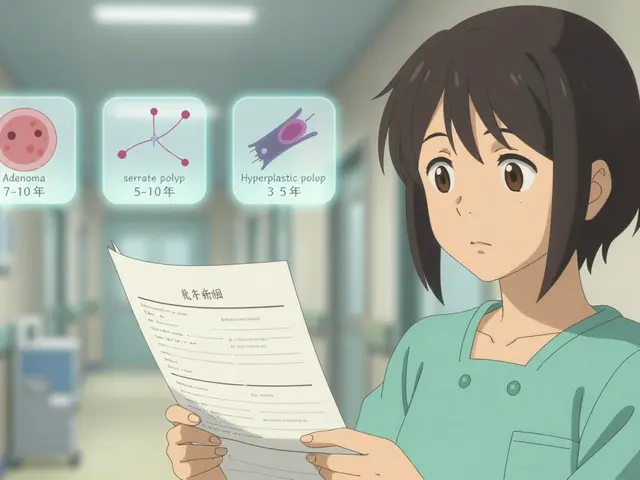

Repeat Colonoscopy: What Your Surveillance Interval Should Be After Polyp Removal

Repeat Colonoscopy: What Your Surveillance Interval Should Be After Polyp Removal

Frank SSS

January 1, 2026 AT 10:32Man, I just read this and my blood pressure spiked. These pharma giants are playing chess while regular folks are stuck buying pills at full price. I mean, a dose counter? That’s not the drug, it’s a plastic gadget. But they list it anyway and lock up the market for years. It’s not innovation-it’s extortion.

And don’t get me started on the Eastern District of Texas. It’s like a patent law casino where the house always wins. Lawyers are getting rich while grandma skips her insulin.

I’m not even mad anymore. I’m just exhausted.

Paul Huppert

January 1, 2026 AT 20:14This is so messed up. I had to choose between my asthma inhaler and groceries last month. The generic was supposed to be cheaper-but it wasn’t even out yet because of some patent on the nozzle. I didn’t even know that was a thing.

Hanna Spittel

January 1, 2026 AT 23:25👀 BIG PHARMA IS RUNNING THE WHOLE SYSTEM. The FDA? In bed with them. The courts? Bought and paid for. The FTC? Just waving a flag. This isn’t capitalism-it’s a cartel with a law degree. #PayForDelay #PharmaCrime

Brady K.

January 3, 2026 AT 22:54Let’s be real: the Hatch-Waxman Act was a noble experiment in good faith. But when you turn a 30-month stay into a 10-year prison sentence for generics, you’re not protecting innovation-you’re weaponizing bureaucracy.

The Orange Book isn’t a registry-it’s a minefield. And the PTAB? Now the Supreme Court’s making it harder to blow up those mines. So we’re stuck with a system where the only people winning are the ones who wrote the rules.

It’s not a market failure. It’s a design flaw. And it’s intentional.

John Chapman

January 5, 2026 AT 09:12Y’all are acting like this is new. It’s been going on for decades. But guess what? Change is coming. The FDA’s new perjury rule? That’s a bomb. And the IPR filings are climbing. Generic companies are getting bolder. The tide’s turning.

Keep fighting. Patients are watching. And we’re not backing down. 💪

Urvi Patel

January 6, 2026 AT 01:34So what you're saying is Americans are too lazy to innovate so they just sue everyone else instead? Funny how the same people who scream about free markets are the first to beg for legal monopolies. This is why the world laughs at US healthcare. No wonder India makes 70% of the world's generics. We're the joke

anggit marga

January 7, 2026 AT 21:05Why are we even talking about this like it's a surprise? America lets corporations write laws. Of course they're using patents to control prices. In Nigeria we just buy generics from India and call it a day. No lawsuits. No drama. Just medicine. Maybe we should just import our pills instead of pretending this system works

Joy Nickles

January 8, 2026 AT 20:45Wait-so the FDA lets companies list patents for… the CAP on the inhaler??!!?? That’s insane. I mean, like, REALLY? Like, I can’t even believe this is legal. I’m not even mad-I’m just… confused? Like, who approved this? Who signed off on this? I need to know who’s responsible because I’m filing a complaint. Like, now. Immediately. Like, right after I finish this comment. This is outrageous. And it’s happening to my mom. And she’s 72. And she needs this drug. And she can’t afford it. And they’re hiding behind a NOZZLE PATENT. I’m done.

Emma Hooper

January 9, 2026 AT 16:42They turned the patent system into a corporate war room. It’s not about protecting ideas anymore-it’s about locking down cash flow like a mafia family controlling a neighborhood. And the worst part? We all play along. We pay. We don’t protest. We just whisper, ‘It’s too complicated.’

But it’s not complicated. It’s criminal. And it’s dressed up in legal jargon so we feel too dumb to argue.

Time to stop being polite and start being pissed.

Martin Viau

January 10, 2026 AT 14:24As a Canadian, I can’t believe we still import half our generics from the U.S. when they’re doing this to their own people. We’ve got price controls here. We don’t let corporations hold entire drug classes hostage for a decade. The fact that the Eastern District of Texas is the patent capital of the world says more about American legal decay than any FDA report ever could.

And don’t even get me started on biosimilars. 78 patents per biologic? That’s not innovation. That’s a legal hedge fund.

Marilyn Ferrera

January 11, 2026 AT 06:06Thank you for this breakdown. I’ve been working in pharmacy for 18 years, and this is exactly what I’ve seen behind the scenes. The Orange Book abuse? It’s systemic. The pay-for-delay settlements? They’re not always bad-sometimes they’re the only path to market. But the serial litigation? That’s pure sabotage.

The FDA’s new perjury rule is the first real step toward accountability. But Congress needs to act. The FTC can’t fix this alone. We need legislation that strips device patents from the Orange Book entirely. No exceptions.

Bennett Ryynanen

January 12, 2026 AT 01:08People act like this is just about money. It’s not. It’s about dignity. My brother has COPD. He needs his inhaler. Every month, he chooses between paying rent or buying his meds. And the reason? A patent on a plastic part that doesn’t even touch his lungs.

We’re not fighting for lower prices. We’re fighting for the right to breathe.

Stop talking about ‘market dynamics.’ Start talking about people.

Chandreson Chandreas

January 12, 2026 AT 14:35It’s wild how the system was built to help, but now it’s just a game of who can file the most patents. Like, imagine if you had to pay someone every time you used a door handle because they patented the hinge. That’s basically what’s happening here.

But hey, at least we got emojis for this chaos 😅