When a doctor switches your medication from a brand-name drug to a generic, most of the time, nothing changes. You get the same pill, same effect, same price. But for some drugs, even a tiny difference can throw your whole treatment off balance. This isn’t theory. It’s happening in clinics across the U.S. every day - especially with drugs that have a narrow therapeutic index (NTI).

What Exactly Is a Narrow Therapeutic Index?

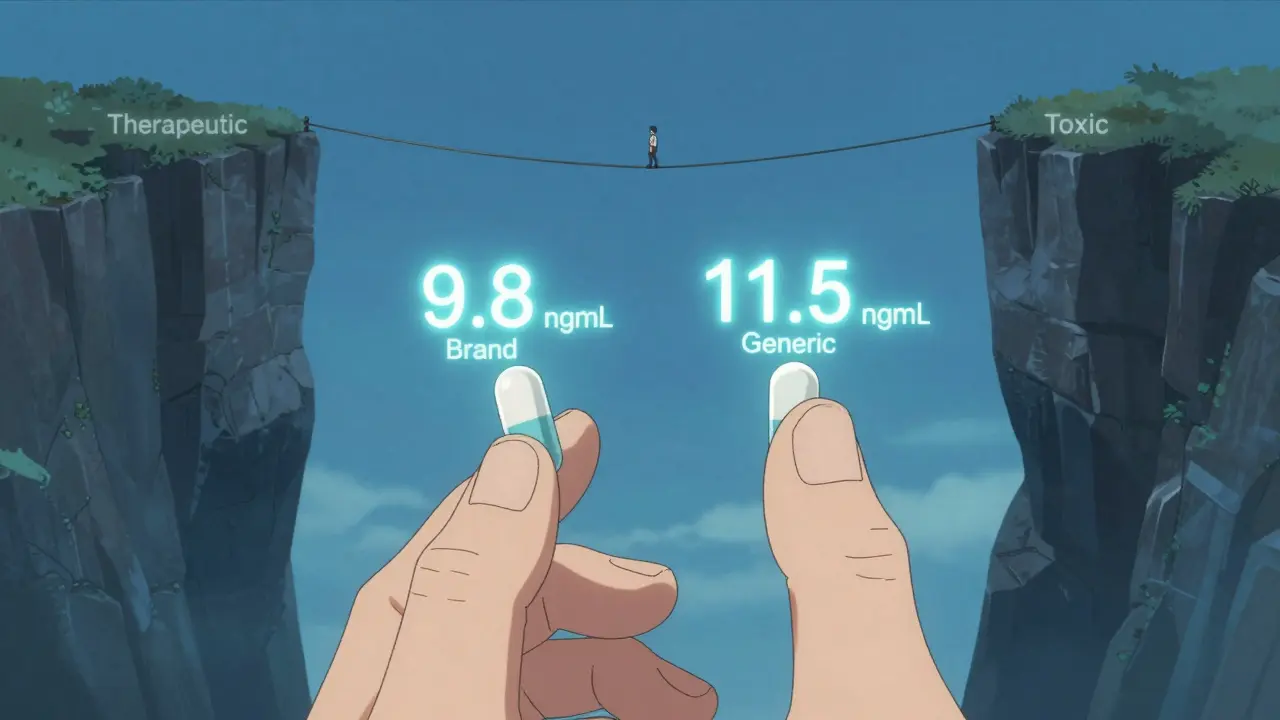

Think of a drug’s therapeutic index as a tightrope. On one side is the dose that treats your condition. On the other side is the dose that causes harm. For most medications, there’s a wide buffer zone - you can miss a dose or take a little extra and nothing bad happens. But for NTI drugs, that buffer is razor-thin. A 10% change in blood concentration might mean your seizure returns, your blood clots, or your transplant gets rejected.

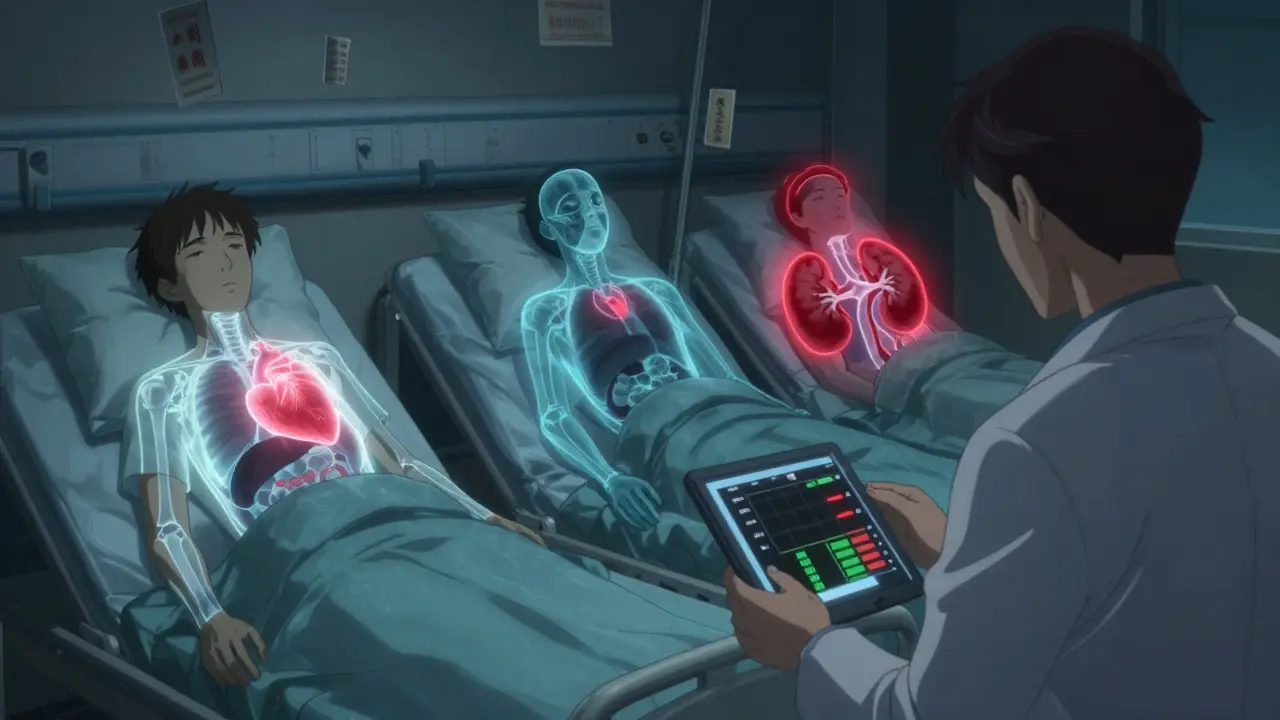

The FDA lists about 15% of commonly prescribed drugs as NTI. These include:

- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Levothyroxine (thyroid hormone)

- Phenytoin and carbamazepine (anti-seizure meds)

- Tacrolimus and cyclosporine (transplant immunosuppressants)

- Digoxin (heart medication)

These aren’t obscure drugs. Millions of Americans take them. And when their pharmacy switches them from one generic to another - or from brand to generic - the body doesn’t always respond the same way.

Why Do Generic Switches Cause Problems?

By law, generic drugs must be bioequivalent to the brand. That means they must deliver 80% to 125% of the active ingredient into your bloodstream compared to the original. Sounds fair, right? But here’s the catch: for NTI drugs, that 45% window is huge. If your target blood level is 10 ng/mL, and the brand keeps you steady at 9.8, a generic that delivers 11.5 could push you into toxicity. Another that delivers 8.1 might leave you under-treated.

It’s not about quality. Most generics are made in the same factories as brands. But small differences in fillers, coatings, or how the pill breaks down in your stomach can change how fast or how much of the drug gets absorbed. For someone on levothyroxine, even a 12.5 mcg shift can cause fatigue, weight gain, or heart palpitations. For someone on warfarin, an INR spike from 2.3 to 4.1 could mean internal bleeding.

Real Cases: What Happens When Switches Go Wrong

Doctors don’t just guess. They see it.

In 2022, a hospital in Boston tracked 87 patients switched from brand-name warfarin to a generic. Within 30 days, 23% needed a dose adjustment. One 68-year-old woman went from stable INRs of 2.5 to 5.2 - she ended up in the ER with a gastrointestinal bleed. Her dose had to be cut by 25%.

Another case: a 42-year-old man with a kidney transplant was switched from brand tacrolimus to a generic. His blood levels dropped 37% in two weeks. His doctors caught it before rejection, but he spent three days in the hospital getting re-stabilized. His transplant team now refuses to switch him unless they monitor levels before and after.

And it’s not just hospitals. A 2023 survey of 1,247 hospital pharmacists found that 68% had seen patients with clinically significant changes after switching NTI generics. Antiepileptic drugs were the most common culprit - 74% of those cases involved seizures returning or worsening.

What Doctors Do About It

There’s no universal rule. But best practices are emerging.

- For levothyroxine: Many endocrinologists avoid switching unless absolutely necessary. If they do, they check TSH levels 6-8 weeks later. A change of more than 10% usually means a dose tweak.

- For warfarin: The American College of Clinical Pharmacy recommends checking INR within 7-14 days after any switch. If the INR is outside 10% of the target, adjust the dose.

- For antiepileptics: Serum drug levels are monitored within two weeks. If levels drop more than 20%, the dose is increased.

- For transplant drugs: Hospitals often require pre- and post-switch blood tests. Some only allow switches if the patient is stable for at least six months.

Some clinics now use clinical decision tools that flag NTI drugs and prompt doctors to order follow-up labs. Others have policies that require patient consent before switching - especially if the patient has been stable for over a year.

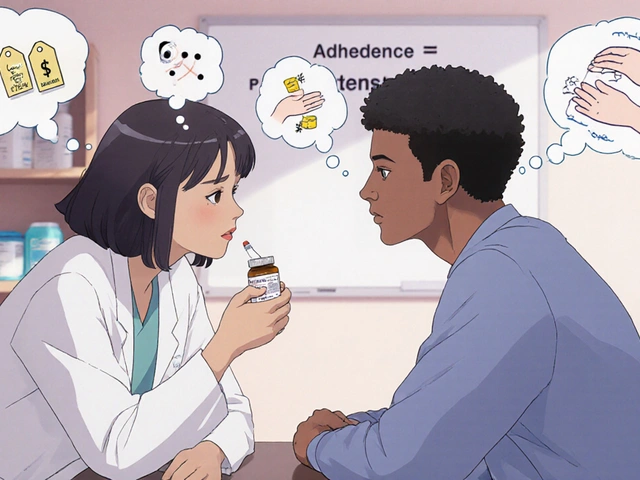

The Insurance Problem

Here’s the real kicker: pharmacies don’t always ask. Insurance companies push for the cheapest generic - even if it’s not the same one you’ve been on. You might get brand-name tacrolimus for six months, then suddenly switch to a different generic because your insurer changed its formulary. No warning. No doctor consultation. Just a new pill in your bottle.

A 2022 survey found that 44% of pharmacists had to switch NTI drugs because of payer mandates. That’s not clinical care - that’s cost control. And it’s risky.

What You Can Do

If you’re on one of these high-risk drugs, here’s what to do:

- Know your drug. Is it an NTI medication? Ask your doctor or pharmacist. If you’re on warfarin, levothyroxine, or a transplant drug, assume it is.

- Ask before switching. If your pharmacy says your prescription was switched, ask: "Is this the same generic I was on?" If not, ask your doctor if you can stay on your current version.

- Request monitoring. After any switch, ask for a blood test 2-4 weeks later. Don’t wait for symptoms.

- Keep a log. Note any new symptoms: fatigue, dizziness, irregular heartbeat, seizures, bruising. Bring it to your next visit.

Some patients have successfully requested a "dispense as written" (DAW) code on their prescription. That tells the pharmacy: "Don’t substitute. Give me exactly what’s on the script." It’s legal. It’s covered under federal law. But you have to ask.

The Future: Tighter Standards Coming?

The FDA is considering a major change. Right now, generics must match brand drugs within 80-125%. But for NTI drugs, they’re proposing a tighter range: 90-111%. That’s a big deal. It means future generics would have to be much more consistent.

Some companies are already ahead of the curve. Teva’s "TacroBell" tacrolimus, for example, shows 32% less variability than standard generics in head-to-head studies. That’s not marketing - that’s science.

But until those standards are mandatory, the burden falls on you and your doctor. Not the pharmacy. Not the insurer. Not the manufacturer.

Bottom Line

Generics save billions. They’re safe - for most drugs. But for NTI medications, they’re not interchangeable. A pill that looks the same isn’t always the same in your body. Dose adjustments aren’t mistakes. They’re necessary safeguards.

If you’re on a high-risk medication, don’t assume everything’s fine after a switch. Ask questions. Demand monitoring. Protect your health. Because when the line between healing and harm is this thin, small changes matter - a lot.

How to Choose OTC Eye Drops for Allergies, Dryness, and Redness

How to Choose OTC Eye Drops for Allergies, Dryness, and Redness

Allergic Reactions to Generics: When to Seek Medical Care

Allergic Reactions to Generics: When to Seek Medical Care

What Is Medication Adherence vs. Compliance and Why It Matters

What Is Medication Adherence vs. Compliance and Why It Matters

Kamagra Oral Jelly vs. Top ED Meds: Sildenafil Comparison Guide

Kamagra Oral Jelly vs. Top ED Meds: Sildenafil Comparison Guide

Top Sativa Strains to Boost Creativity & Productivity

Top Sativa Strains to Boost Creativity & Productivity

Suzette Smith

February 13, 2026 AT 05:19Skilken Awe

February 13, 2026 AT 17:06andres az

February 14, 2026 AT 01:30Sonja Stoces

February 15, 2026 AT 15:13Rob Turner

February 16, 2026 AT 15:15Kristin Jarecki

February 17, 2026 AT 09:48Jonathan Noe

February 18, 2026 AT 12:27Jim Johnson

February 19, 2026 AT 04:12Alyssa Williams

February 20, 2026 AT 23:59Ojus Save

February 21, 2026 AT 22:55