What bioavailability studies actually measure

When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name drug. But behind that simple swap is a rigorous scientific process designed to prove the two are truly interchangeable. The key to that proof lies in bioavailability studies. These aren’t guesswork or shortcuts-they’re precise, controlled experiments that measure how much of the drug enters your bloodstream and how fast it gets there.

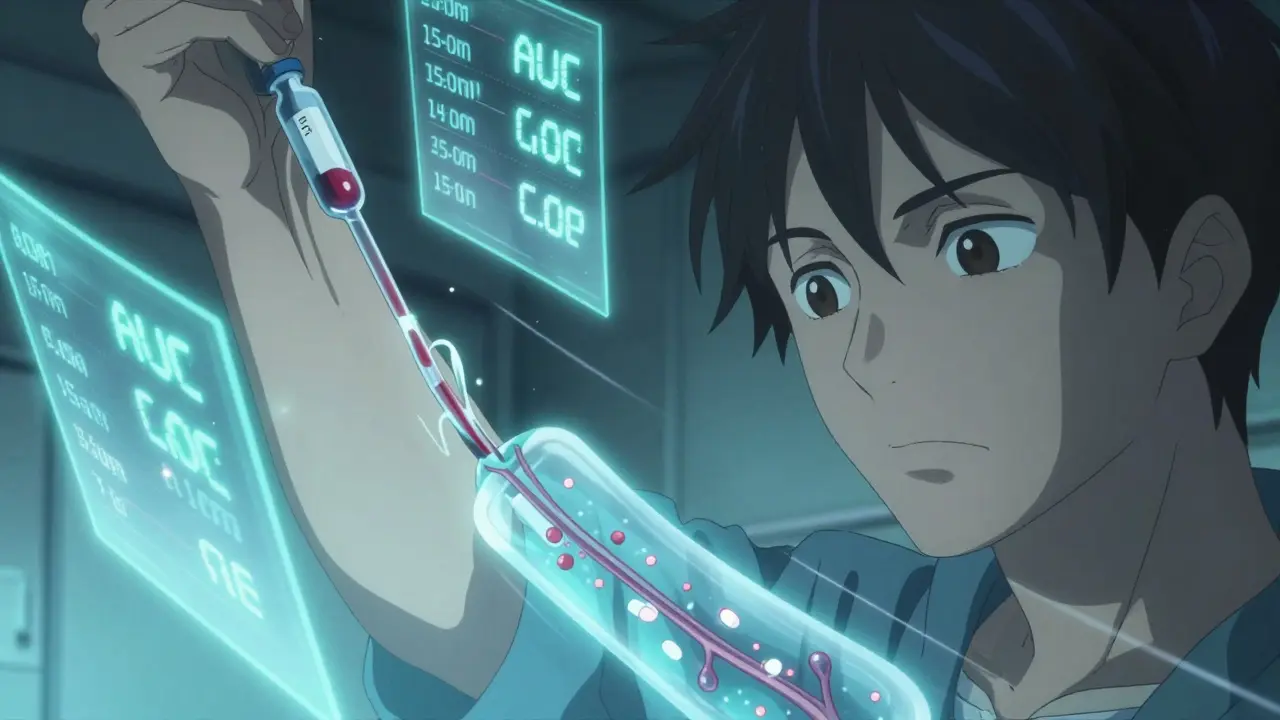

Bioavailability isn’t just about whether the drug is present. It’s about the rate and extent of absorption. Two drugs can have the same active ingredient, but if one dissolves slowly in your stomach while the other zips through, they won’t behave the same way in your body. That’s why scientists track two main numbers: AUC (Area Under the Curve) and Cmax (Maximum Concentration). AUC tells you the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time. Cmax shows you the highest level it reaches. Together, they paint a full picture of how the drug moves through your system.

There’s also Tmax-the time it takes to hit that peak concentration. If a generic version reaches peak levels too fast or too slow compared to the brand, it could mean differences in how quickly symptoms are relieved or how long effects last. For drugs like seizure medications or blood thinners, even small timing shifts matter.

Why the 80-125% rule exists

The FDA doesn’t require generics to match brand-name drugs perfectly. Instead, they use a range: 80% to 125%. That means the generic’s AUC and Cmax values must fall within 20% above or below the brand’s. At first glance, that sounds wide. But this isn’t arbitrary. It’s based on decades of clinical data showing that a 20% difference in absorption usually doesn’t affect how well a drug works or how safe it is for most people.

Here’s how it works in practice: if a brand-name drug gives you an AUC of 100 units, a generic is approved if its AUC lands between 80 and 125. The same applies to Cmax. But here’s the catch-the FDA doesn’t just look at averages. They calculate a 90% confidence interval. That means they’re 90% sure the true difference between the two drugs falls within that 80-125% range. It’s not enough for the average to be close; the entire range of possible values must fit inside the limits.

For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, digoxin, or levothyroxine-the rules tighten. The acceptable range shrinks to 90-111%. Why? Because tiny changes in blood levels can lead to serious side effects. A slightly too-high dose of warfarin can cause dangerous bleeding. A slightly too-low dose of levothyroxine can leave you fatigued or increase your risk of heart problems. These drugs demand extra precision.

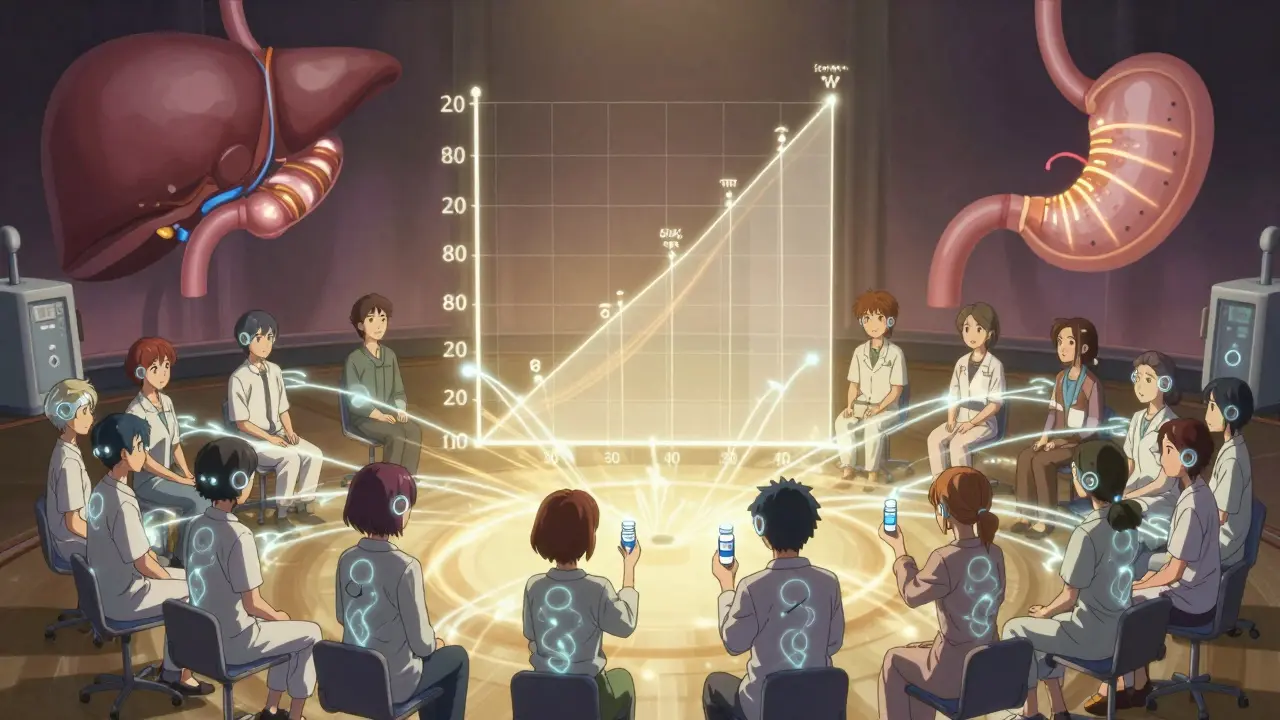

How the studies are done

These aren’t lab experiments on petri dishes. They’re real human trials. Typically, 24 to 36 healthy volunteers participate. They’re given either the brand-name drug or the generic in the first phase, then switched to the other after a washout period-usually five times the drug’s half-life-to make sure nothing from the first dose lingers.

Over the next 24 to 72 hours, researchers draw blood every 15 to 60 minutes. That’s dozens of vials per person. The blood is analyzed using highly sensitive methods to measure exactly how much drug is in the plasma. The lab techniques must be validated to within 85-115% accuracy. Even small errors here can throw off the whole study.

Design matters too. Most studies use a crossover model: each person takes both versions. This reduces variability between subjects. One person might naturally absorb drugs faster than another, but if they take both the brand and generic, those differences cancel out when comparing the two.

For complex formulations-like extended-release pills or patches-the testing gets harder. Instead of just one AUC and Cmax, researchers must check multiple time points. For a once-daily extended-release tablet, they need to prove the drug releases slowly and evenly over 24 hours, not just that the total amount absorbed is the same.

When bioequivalence isn’t enough

Most of the time, bioequivalence works. The FDA has approved over 15,000 generic drugs since 1984, and 90% of Americans can’t tell the difference between brand and generic in real-world use. But there are exceptions.

Take levothyroxine. Thousands of patients rely on it to regulate their thyroid. Even small variations in absorption can throw off hormone levels. Some patients report fatigue, weight gain, or heart palpitations after switching generics. The FDA tracks these reports, but in most cases, the issue isn’t the drug’s bioavailability-it’s inconsistent dosing across batches, or patient adherence. Still, many doctors prefer to keep patients on the same brand or generic to avoid any risk.

Another challenge is highly variable drugs. Some people absorb them quickly, others slowly. For these, the standard 80-125% range doesn’t work well. The FDA now allows something called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). If a drug shows high variability in trials, the acceptable range can widen to 75-133%. This was used for the approval of a generic version of tacrolimus, a critical transplant drug. Without RSABE, that generic might never have been approved.

Then there are topical products, inhalers, and injectables. For a cream or gel, you can’t just measure blood levels. You might need to test skin thinning or immune response. For inhalers, it’s about how much drug reaches the lungs, not the bloodstream. These require entirely different testing methods-and they’re harder to standardize.

What happens when a study fails

Not every generic passes. And when it doesn’t, it doesn’t get approved. One study found a generic with an AUC ratio of 1.16-16% higher than the brand. At first glance, that sounds fine. But the 90% confidence interval went up to 1.30, which is outside the 1.25 limit. So it failed. Even though the average was close, the range of possible values was too wide.

Another case showed a generic with 10% lower bioavailability (AUC ratio of 0.90). That’s within the 80-125% range, so it passed. But what if that 10% drop happened in a drug where every percentage point counts? That’s why regulators watch for trends. If multiple generics for the same drug keep hovering near the 80% limit, the FDA may ask for more data.

Companies sometimes re-formulate and resubmit. They tweak the inactive ingredients-fillers, binders, coatings-to change how fast the pill dissolves. Sometimes, it takes three or four tries before a generic clears the bar. That’s why some generics take years to hit the market, even after the patent expires.

The bigger picture: cost, access, and trust

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system over $300 billion a year. They’re why a 30-day supply of lisinopril costs $4 instead of $150. But trust is fragile. Some patients, and even some doctors, still hesitate. They worry about switching from a brand they’ve used for years.

Studies show that in 97% of cases, generics perform just like the brand. But the 3% where things feel different? Those stories stick. A cardiologist might see three patients over five years who had palpitations after switching to a generic amlodipine. That’s rare-but it’s enough to make someone cautious.

The FDA and independent experts agree: for most drugs, the bioequivalence system works. It’s not perfect, but it’s the best tool we have. And it’s constantly improving. New tools like artificial intelligence are being tested to predict bioequivalence from formulation data alone, which could cut down on human trials. The FDA’s 2023 collaboration with MIT showed AI could predict AUC ratios with 87% accuracy across 150 drugs.

For now, though, the gold standard remains blood samples, controlled trials, and hard numbers. Because when it comes to your health, you don’t want guesswork. You want proof.

What you can do as a patient

If you’ve been on a brand-name drug for years and your pharmacy switches you to a generic, don’t panic. Most of the time, you won’t notice a difference. But pay attention. If you feel new side effects-dizziness, fatigue, irregular heartbeat, or worsening symptoms-talk to your doctor. Don’t assume it’s all in your head.

Some states require your doctor to approve substitutions for certain drugs, especially those with narrow therapeutic windows. Ask if your prescription is one of them.

And if you’re prescribed a drug where consistency matters-like thyroid meds, seizure drugs, or blood thinners-consider asking your doctor to write "Dispense as Written" or "Do Not Substitute" on the prescription. It’s your right.

Generics aren’t inferior. They’re rigorously tested. But your body is unique. If something feels off, speak up. The system works best when patients and doctors work together with the data.

Sirolimus and Wound Healing: When to Start After Surgery

Sirolimus and Wound Healing: When to Start After Surgery

What Is a Mentat? The Real‑World Meaning Behind Dune’s Human Computers

What Is a Mentat? The Real‑World Meaning Behind Dune’s Human Computers

Buy Online Cheap Generic Ativan: What You Need to Know Before You Order

Buy Online Cheap Generic Ativan: What You Need to Know Before You Order

How and Where to Buy Keppra Online: Safe Ordering & Tips

How and Where to Buy Keppra Online: Safe Ordering & Tips

Understanding Tumor Growth: Cancer Cell Biology, Mitosis, and Angiogenesis Explained

Understanding Tumor Growth: Cancer Cell Biology, Mitosis, and Angiogenesis Explained

Bridget Molokomme

February 2, 2026 AT 22:49Bob Hynes

February 4, 2026 AT 16:40Eli Kiseop

February 5, 2026 AT 08:17Ellie Norris

February 6, 2026 AT 03:34Marc Durocher

February 6, 2026 AT 10:50larry keenan

February 8, 2026 AT 03:06Akhona Myeki

February 8, 2026 AT 23:19Chinmoy Kumar

February 9, 2026 AT 22:37jay patel

February 10, 2026 AT 02:36Ansley Mayson

February 10, 2026 AT 17:15phara don

February 11, 2026 AT 10:24