When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it’s safe and effective? The answer lies in a statistical rule most people have never heard of: the 80-125% rule. This isn’t about how much active ingredient is in the pill. It’s about how your body absorbs and uses that ingredient. And it’s the reason millions of people take generic drugs every day without knowing the science behind them.

What the 80-125% Rule Actually Means

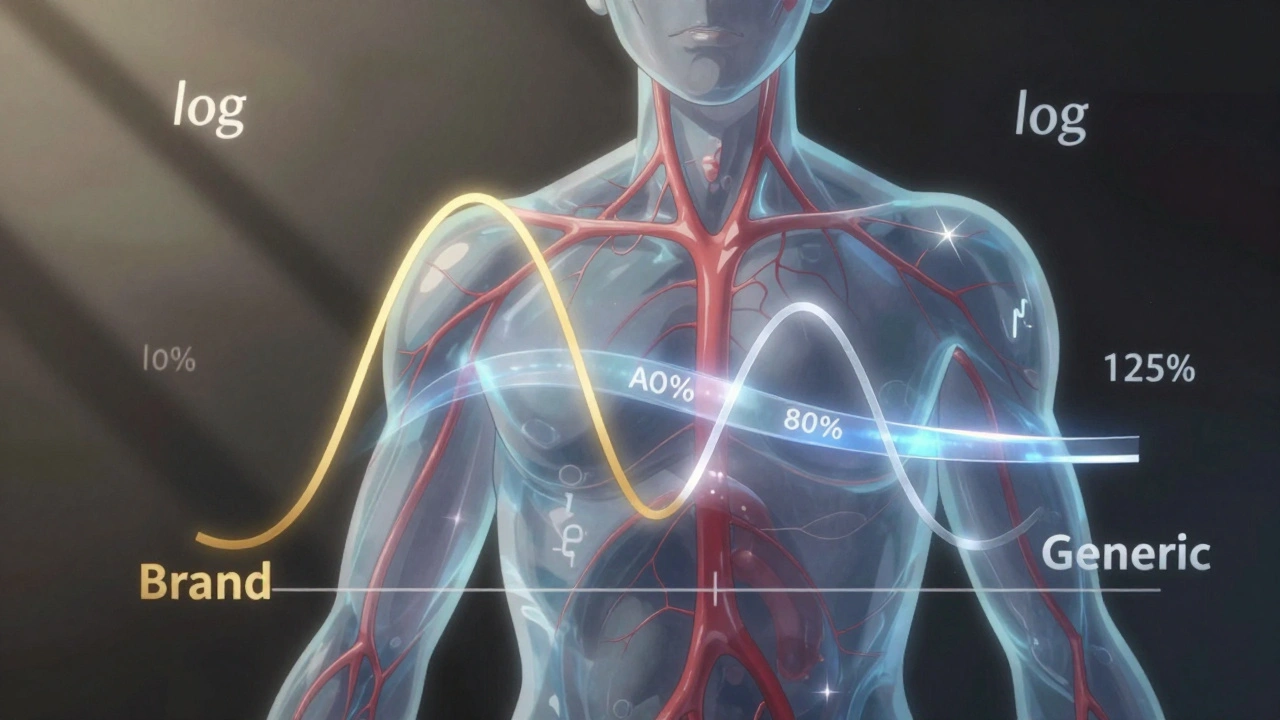

Many people think the 80-125% rule means a generic drug can contain anywhere from 80% to 125% of the active ingredient compared to the brand-name version. That’s wrong. The rule doesn’t refer to the amount of drug in the tablet. It refers to how much of that drug actually gets into your bloodstream.

Regulators measure two key things: Area Under the Curve (AUC), which tells you how much drug your body is exposed to over time, and Cmax, which tells you how fast it reaches its highest level. These aren’t measured by weighing pills-they’re measured in clinical studies by taking blood samples from healthy volunteers after they take the drug.

The 80-125% rule says that the 90% confidence interval of the ratio between the generic and brand-name drug’s AUC and Cmax must fall entirely within that range. That’s it. If even one point of that interval goes outside 80% or 125%, the drugs aren’t considered bioequivalent. And no, this isn’t a random number. It came from decades of data, expert panels, and clinical experience.

Why Logarithms and Confidence Intervals?

Pharmacokinetic data doesn’t behave like normal numbers. Drug levels in the blood don’t follow a straight line-they follow a curve that’s skewed. That’s why scientists use logarithmic transformation. On a log scale, a 20% decrease and a 20% increase look the same. So 80% becomes -0.2231 and 125% becomes +0.2231. This symmetry makes the math work.

Why a 90% confidence interval instead of the more common 95%? Because it allows for a 5% error on each end. That adds up to a 10% total chance of being wrong. That’s considered acceptable in this context because the goal isn’t to prove exact equality-it’s to prove that any difference is too small to matter clinically. Traditional hypothesis testing doesn’t work here. With enough people in a study, even a 1% difference can look statistically significant. But 1% isn’t clinically meaningful. Confidence intervals solve that problem.

How This Rule Got Started

In the 1970s, the FDA used a simple ±20% rule. But experts realized it didn’t account for how drugs behave in the body. In 1986, after a major hearing, they switched to the 80-125% rule based on log-transformed data. The decision wasn’t based on a giant clinical trial. It was based on expert judgment: differences under 20% in absorption were unlikely to cause real-world problems.

Since then, the rule has held up. A 2022 analysis of 214 studies found no meaningful differences in outcomes across 37 drug classes when products met the 80-125% standard. The FDA has approved over 14,000 generic drugs under this rule since 1984. And post-market surveillance shows that only 0.34% of those generics ever needed label changes due to bioequivalence concerns.

Where the Rule Breaks Down

Not all drugs play nice with the 80-125% rule. Some drugs have a very narrow window between being effective and being dangerous. Think warfarin, levothyroxine, or certain anti-seizure medications. For these, regulators use tighter limits: 90-111%. That’s because even a 10% drop in exposure could mean a seizure returns, or a blood clot forms.

Then there are highly variable drugs-ones where people’s bodies absorb them differently from one day to the next. For these, the standard rule doesn’t work well. The European Medicines Agency and the FDA now use something called scaled average bioequivalence (SABE). It lets the acceptance range widen based on how much the drug varies in people. For example, Cmax for a highly variable drug might be allowed to go as high as 143% if the variability is high enough.

Complex drugs like inhalers, topical creams, or extended-release pills also challenge the rule. That’s why the FDA launched its Complex Generics Initiative in 2018. These aren’t simple pills you swallow. Their absorption depends on how they’re made, how they dissolve, even how they interact with food. The 80-125% rule was built for simple oral tablets. It’s still being adapted for everything else.

Common Misconceptions

A 2022 survey found that 63% of community pharmacists thought the 80-125% rule meant generics could contain 80% to 125% of the active ingredient. That’s not true. Generic pills are manufactured to contain 95-105% of the labeled amount-just like brand-name pills. The rule applies to what happens after you swallow it, not what’s in the capsule.

Patients worry too. On forums like Drugs.com, people ask if their generic seizure medication is “only 80% as strong.” But the data doesn’t back that up. A 2022 survey of 412 neurologists found only 4% believed bioequivalence standards caused problems with anti-epileptic drugs. Most issues came from switching brands too often, not from the 80-125% rule itself.

What Happens in a Bioequivalence Study

Before a generic drug hits the market, it goes through a crossover study. About 24 to 36 healthy volunteers take both the brand and generic versions in random order, with a washout period in between. Blood is drawn over 24 to 72 hours. The data is log-transformed, the geometric mean ratio is calculated, and the 90% confidence interval is built.

The FDA requires both AUC and Cmax to pass. One can’t compensate for the other. If the generic gets absorbed faster but less completely, it fails. If it’s absorbed more slowly but fully, it still fails. Both parts matter.

For high-variability drugs, they use replicate designs-giving the same person the drug multiple times. That can mean 50 to 100 participants instead of 24. It’s expensive. Bioequivalence studies cost $2 to $5 million and add 18 to 24 months to development time. That’s why some companies push for waivers-like when a drug dissolves in water the same way as the brand, and meets strict dissolution criteria. The FDA now allows those for certain immediate-release pills.

Global Harmonization and the Future

The U.S., Europe, Canada, China, and the WHO all use nearly identical rules. That’s rare in global regulation. It means a generic drug approved in the U.S. can often be submitted to Europe with minimal changes. This harmonization is why the global generic drug market is worth over $227 billion.

But change is coming. The FDA’s 2023-2027 plan includes $15 million for “model-informed bioequivalence”-using computer simulations to predict how a drug behaves without testing it in people. That could cut costs and speed up approvals.

And then there’s pharmacogenomics. We now know that genes affect how people metabolize drugs. Someone with a slow liver enzyme might absorb a drug differently than someone with a fast one. In the future, bioequivalence might need to account for genetic subgroups. That’s still years away, but it’s already being researched.

For now, the 80-125% rule works. It’s not perfect. It’s not based on clinical trials. But it’s stood the test of time. And for most people, most of the time, it ensures that the generic pill you pick up is just as safe and effective as the brand.

Does the 80-125% rule mean generic drugs are weaker than brand-name drugs?

No. The rule doesn’t say anything about how much active ingredient is in the pill. Generics must contain 95-105% of the labeled amount, same as brand-name drugs. The 80-125% range refers to how much of that drug gets into your bloodstream-measured by AUC and Cmax in clinical studies. If the confidence interval falls within that range, your body absorbs the drug similarly to the brand. That’s why millions of people safely switch to generics every day.

Why is a 90% confidence interval used instead of 95%?

A 90% confidence interval allows for a 5% error on each side, totaling a 10% chance of being wrong. This is intentional. The goal isn’t to prove the drugs are identical-it’s to prove that any difference is too small to matter in real-world use. A 95% interval would be too strict and could block generics that are clinically equivalent. The 90% level was chosen based on expert consensus that differences under 20% in absorption are unlikely to affect patient outcomes.

Are there drugs that don’t follow the 80-125% rule?

Yes. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, and some anti-seizure medications-require tighter limits: 90-111%. That’s because even small changes in blood levels can cause serious side effects or loss of effectiveness. Highly variable drugs, where people’s absorption rates differ widely, may use scaled bioequivalence, which adjusts the range based on how much the drug varies between individuals. These exceptions exist because the standard rule doesn’t work for all drugs.

Can a generic drug fail the 80-125% rule and still be safe?

If a drug fails the 80-125% rule, regulators won’t approve it. That’s because the rule is designed to catch clinically meaningful differences. A failed study means the body absorbs the drug too differently from the brand. Even if no harm has been seen yet, regulators err on the side of caution. There’s no guarantee that a failed product would be safe in all patients, especially those with other health conditions. So it’s not approved.

Why do some people say their generic medication doesn’t work as well?

Most of the time, it’s not the bioequivalence rule at fault. The generic drug passed all the tests. But switching between different generic brands-or between generic and brand-can cause issues if the formulations differ in fillers, coatings, or release rates. These aren’t covered by the 80-125% rule. For drugs like anti-seizure medications, even small changes in how fast the drug dissolves can matter. That’s why some doctors recommend sticking with one brand or generic version. It’s not about strength-it’s about consistency.

Epivir (Lamivudine) vs Other HIV Drugs: Detailed Comparison

Epivir (Lamivudine) vs Other HIV Drugs: Detailed Comparison

What to Do If a Child Swallows the Wrong Medication: Immediate Steps That Save Lives

What to Do If a Child Swallows the Wrong Medication: Immediate Steps That Save Lives

Explore Top Alternatives to Canada Meds Plus for Affordable Medications

Explore Top Alternatives to Canada Meds Plus for Affordable Medications

How to Buy Cheap Generic Metformin Online Safely

How to Buy Cheap Generic Metformin Online Safely

Peru Balsam: The Life-Changing Dietary Supplement You Need to Experience

Peru Balsam: The Life-Changing Dietary Supplement You Need to Experience

Christian Landry

December 8, 2025 AT 20:48Maria Elisha

December 10, 2025 AT 19:23Lisa Whitesel

December 11, 2025 AT 07:11Mona Schmidt

December 11, 2025 AT 22:38Larry Lieberman

December 12, 2025 AT 23:14Tejas Bubane

December 14, 2025 AT 17:32Ajit Kumar Singh

December 15, 2025 AT 01:22Angela R. Cartes

December 15, 2025 AT 21:24Katie Harrison

December 16, 2025 AT 09:05Guylaine Lapointe

December 16, 2025 AT 10:52Andrea Beilstein

December 18, 2025 AT 07:16