When you take a pill once a day instead of three times, it’s not just convenience-it’s science. Modified-release (MR) formulations are designed to control how and when a drug enters your bloodstream. They’re used in everything from blood pressure pills to ADHD medications. But getting these drugs approved as generics isn’t as simple as copying a tablet. There’s a whole layer of testing called bioequivalence that’s far more complex than for regular pills. If you’re wondering why some generic MR drugs work differently than others-or why some get rejected by regulators-this is why.

What Makes Modified-Release Formulations Different?

Immediate-release (IR) drugs dump their entire dose into your system quickly. That’s fine for some medicines, but for others, it causes spikes and crashes in blood levels. Too much at once can cause side effects. Too little later on means the drug stops working. Modified-release formulations solve this by slowly releasing the drug over hours. Think of it like a time-release capsule: one part releases fast, another part drags out over the day.

These aren’t just fancy pills. They’re engineered systems. Some use coatings that dissolve at different pH levels. Others have tiny beads inside a capsule that release at staggered intervals. Some even resist being broken down by alcohol. That last part matters-drinking while on certain extended-release opioids can cause a dangerous surge of drug into the bloodstream. That’s called dose dumping, and it’s led to seven drug withdrawals between 2005 and 2015.

Today, about 35% of all approved generic drugs are modified-release. In the U.S. alone, they make up $65 billion in annual sales. That’s not small change. It’s a huge chunk of the market, and regulators treat them like high-stakes products.

Why Bioequivalence for MR Drugs Isn’t Just About AUC and Cmax

For regular pills, bioequivalence is pretty straightforward: compare the total drug exposure (AUC) and the peak concentration (Cmax) between the brand and generic. If both are within 80-125% of each other, you’re good.

But for MR drugs? That’s not enough.

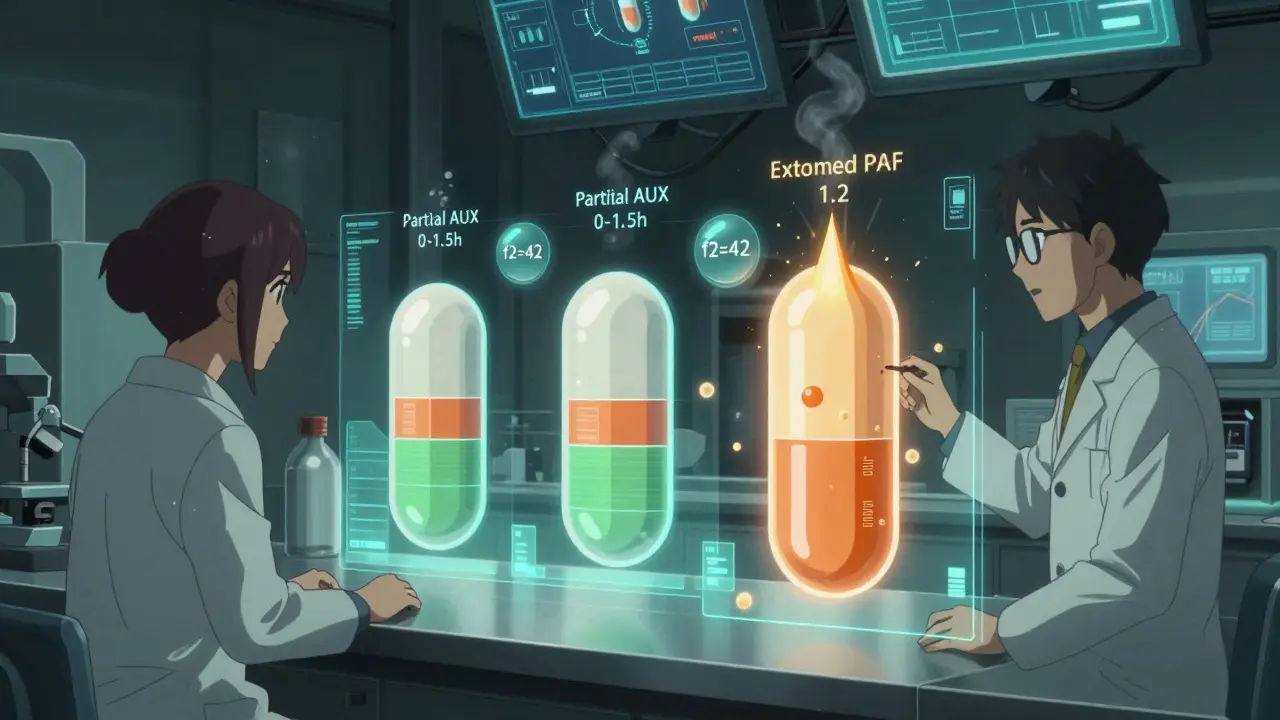

Take a drug like Ambien CR. It has two phases: one that kicks in fast to help you fall asleep, and another that lasts longer to keep you asleep. If the generic only matches the overall exposure but messes up the timing of those two phases, you might wake up in the middle of the night-or feel groggy in the morning. That’s why regulators require partial AUC measurements.

The FDA requires testing two time windows: from zero to 1.5 hours (the fast part) and from 1.5 hours to infinity (the slow part). Both have to be within 80-125%. One failure, and the application gets rejected. In fact, 22% of MR generic applications between 2018 and 2021 were turned down because they didn’t measure the right timepoints.

And it’s not just timing. For drugs with high variability-like warfarin or certain seizure medications-the acceptance range tightens to 90-111%. That’s because even small differences can cause serious harm. A 10% drop in blood levels might mean a seizure. A 10% spike might mean bleeding.

How Regulators Compare MR Products: FDA vs. EMA

The FDA and EMA (Europe’s drug agency) don’t see eye to eye on everything. And that creates real headaches for drugmakers trying to sell globally.

The FDA says: Single-dose studies are better. Why? Because they show how the drug behaves when there’s no buildup. Multiple doses can mask problems with release patterns. Since 2015, 92% of approved extended-release generics used single-dose studies.

The EMA, on the other hand, sometimes still requires steady-state studies-where patients take the drug daily for days or weeks until levels stabilize. They argue this better reflects real-world use, especially for drugs that accumulate.

But here’s the conflict: a 2018 paper by Dr. Lawrence Lesko called the EMA’s steady-state requirement “lacking scientific justification for most products.” Meanwhile, Dr. Donald Mager argues it’s necessary for drugs with high accumulation.

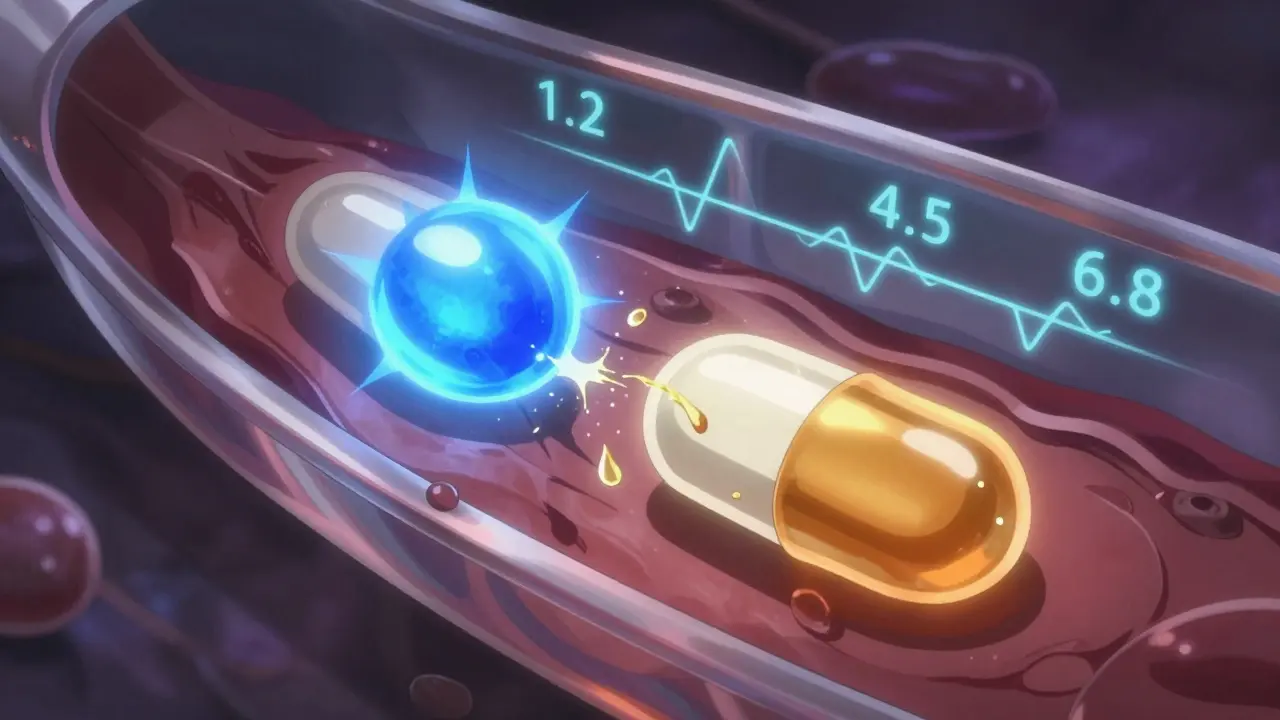

Dissolution testing is another battleground. The FDA demands testing at three pH levels-1.2 (stomach), 4.5 (upper intestine), and 6.8 (lower intestine)-for extended-release tablets. The EMA accepts two. And for beaded capsules? The FDA only requires one condition. That inconsistency means a product that passes in the U.S. might fail in Europe, and vice versa.

The Hidden Costs and Failures Behind Generic MR Drugs

Developing a generic MR drug costs $5-7 million more than a regular one. Why? Because the studies are harder, longer, and more expensive.

A single-dose MR bioequivalence study runs $1.2-1.8 million. Compare that to $0.8-1.2 million for a standard IR study. And it’s not just money. It’s time. For highly variable drugs, using the Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE) method adds 6-8 months to development. That’s because you need more volunteers, more blood draws, and complex statistical modeling.

And failures are common. One formulation scientist at Teva reported that 35-40% of early-stage oxycodone ER generics failed dissolution testing across the three pH levels. A generic version of Concerta (methylphenidate ER) was rejected in 2012 because it didn’t match the brand’s release profile in the first two hours-critical for ADHD patients who need quick symptom control.

But success stories exist. Sandoz got its extended-release tacrolimus approved using a biowaiver based on dissolution similarity (f2=68 at pH 6.8). That saved $1.5 million and 10 months. How? By showing their tablet released drug at nearly the same rate as the brand under all conditions.

What It Takes to Get It Right

There’s no shortcut. Getting MR bioequivalence right requires:

- Advanced dissolution testing-often using USP Apparatus 3 or 4, not the standard Apparatus 2

- Pharmacokinetic modeling software like Phoenix WinNonlin or NONMEM

- Statistical expertise to handle RSABE and partial AUC calculations

- Understanding of product-specific guidances (PSGs)-the FDA has over 150 of them for MR drugs

And the learning curve? According to a 2022 survey by the International Society for Pharmacokinetics, it takes 12-18 months of training just to become competent in MR BE study design.

Most of this work is done by big pharma and large contract research organizations (CROs). Only 3% of MR BE studies are done by small biotechs. The cost and complexity are just too high.

The Future: IVIVC, PBPK, and What’s Next

The field is moving beyond just testing. The FDA now accepts in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) models for some MR products. That means if a tablet’s dissolution profile perfectly predicts how it behaves in the body, you might not need a full human study. Twelve products have been approved this way since 2019.

Even more advanced is physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. It simulates how a drug moves through the body based on anatomy, pH, blood flow, and enzyme activity. A 2022 DIA survey found 68% of major pharma companies now use PBPK for MR development.

And regulators are catching up. The FDA plans to release a new guidance in 2024 on complex MR systems-like gastroretentive tablets that float in the stomach, or multiparticulate systems with dozens of tiny beads. These are the future of chronic disease management.

By 2028, IQVIA predicts MR formulations will make up 42% of all prescription sales. Aging populations, chronic illnesses, and demand for once-daily dosing are driving this growth. But with growth comes risk. A 2016 study in Neurology found that 18% of generic extended-release antiepileptic drugs had higher seizure rates than the brand-even though they passed standard bioequivalence tests.

That’s the real challenge: meeting the numbers doesn’t always mean matching the experience.

Why can’t we just use the same bioequivalence rules for modified-release drugs as for immediate-release ones?

Because modified-release drugs are designed to release the drug over time, not all at once. If you only compare total exposure (AUC) and peak concentration (Cmax), you might miss critical differences in how fast or when the drug is released. For example, a generic might have the same overall AUC as the brand, but release too much too early or too little too late-leading to side effects or loss of effectiveness. That’s why regulators require partial AUC measurements and dissolution profile matching.

What is dose dumping, and why is it a concern with extended-release drugs?

Dose dumping happens when alcohol or other substances cause an extended-release drug to release its entire dose at once instead of gradually. This can lead to dangerous spikes in blood levels. For example, drinking while taking certain opioid painkillers can cause overdose. The FDA requires alcohol interaction testing for all ER products containing 250 mg or more of active ingredient. Between 2005 and 2015, seven such products were pulled from the market because of this risk.

Why do some generic MR drugs work differently than the brand even if they’re bioequivalent?

Bioequivalence standards focus on average blood levels, not individual patient response. Some patients are more sensitive to timing or small variations in release. A 2016 study found that 18% of generic extended-release antiepileptic drugs had higher seizure rates than the brand, even though they passed standard bioequivalence tests. This suggests that current methods may not capture all clinical differences, especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows.

How do FDA and EMA guidelines differ on bioequivalence testing for MR drugs?

The FDA primarily uses single-dose fasting studies and requires partial AUC measurements for multiphasic drugs. It also demands dissolution testing at three pH levels (1.2, 4.5, 6.8) for tablets. The EMA sometimes requires steady-state studies and focuses more on metrics like half-value duration and midpoint duration time. It also accepts a lower f2 similarity factor for biowaivers and doesn’t always require three pH tests. These differences mean a product approved in the U.S. might not be approved in Europe, and vice versa.

What is RSABE, and why is it used for some MR drugs?

RSABE stands for Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence. It’s used for highly variable drugs-where the brand’s own blood levels vary a lot between patients (within-subject CV >30%). Standard 80-125% limits are too strict here, so RSABE widens the range based on the brand’s variability, up to a cap of 57.38%. This prevents rejecting good generics just because the drug is naturally inconsistent. It’s required for drugs like warfarin, clopidogrel, and some antiepileptics.

Can a generic MR drug get approved without doing a human bioequivalence study?

Yes, under certain conditions. If the drug’s dissolution profile matches the brand across all required pH levels and conditions, and if there’s a validated in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC), regulators may grant a biowaiver. This is rare and only applies to a few products, like some extended-release tacrolimus and paliperidone formulations. It saves time and money, but requires extensive lab data and modeling.

What’s the biggest challenge in developing a generic modified-release drug?

The biggest challenge is replicating the release profile exactly. Even small changes in coating thickness, bead size, or excipient composition can alter how the drug releases. Many developers fail because their dissolution profile doesn’t match the brand across all three pH levels. It’s not just about the active ingredient-it’s about the entire delivery system. That’s why 35-40% of early-stage oxycodone ER generics fail initial testing.

Understanding Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome and Its Link to Pancreatic Tumors

Understanding Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome and Its Link to Pancreatic Tumors

Feldene (Piroxicam) vs Topical NSAID Alternatives - Pros, Cons & Best Uses

Feldene (Piroxicam) vs Topical NSAID Alternatives - Pros, Cons & Best Uses

How to Involve Grandparents and Caregivers in Pediatric Medication Safety

How to Involve Grandparents and Caregivers in Pediatric Medication Safety

Nebulizers vs. Inhalers: Which One Really Works Better for Asthma and COPD?

Nebulizers vs. Inhalers: Which One Really Works Better for Asthma and COPD?

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and Urinary Difficulty: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and Urinary Difficulty: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

Jeremy Williams

February 20, 2026 AT 04:32Look, I work in regulatory affairs for a mid-sized pharma firm. The MR bioequivalence mess is real. We spent 18 months on a single oxycodone ER candidate. Three pH dissolution tests? Check. Partial AUCs? Check. RSABE modeling? Double check. And still, the FDA asked for a second study because the f2 value at pH 4.5 was 63. Not 65. That’s not science - that’s ritual. We lost $2.1M and two team members to burnout. And this is for a drug that’s been on the market for 20 years.

Ellen Spiers

February 20, 2026 AT 17:34The regulatory divergence between FDA and EMA is not merely technical - it is epistemologically incoherent. The FDA’s reliance on single-dose studies presumes a pharmacokinetic equilibrium that is empirically untenable for drugs with significant accumulation kinetics (e.g., tacrolimus, sertraline). The EMA’s steady-state paradigm, while logistically burdensome, aligns with first-principles pharmacology. To privilege bioavailability metrics over bioeffectiveness is to mistake the map for the territory.

Marie Crick

February 21, 2026 AT 23:22So let me get this straight - we’re letting generics into the market that might cause seizures… just because they hit a number? That’s not healthcare. That’s gambling. And the people paying the price? Us. The patients. The ones who don’t have a lab or a regulatory team on speed dial.

Maddi Barnes

February 22, 2026 AT 08:13Y’all know what’s wild? The fact that we have 150+ product-specific guidances but zero standardization on how to test bead release in a capsule. Like, imagine if every iPhone charger had a different plug shape and Apple said, "Just test each one individually." That’s what we’re doing with MR drugs. And then we wonder why patients get confused. 😒 Also - why is no one talking about how big pharma uses these rules to block generics? The system is rigged. #PharmaCrisis

Tommy Chapman

February 24, 2026 AT 01:31Europe is soft. FDA’s got balls. If you can’t pass three pH tests, you don’t deserve to be on the market. This isn’t about money - it’s about safety. I don’t care if your generic costs $0.02 a pill. If it dumps dose when someone has a beer, it’s a death trap. American standards aren’t perfect - but they’re not stupid either.

Irish Council

February 25, 2026 AT 14:25They say dose dumping is rare. But did you know the FDA quietly approved a generic ER oxycodone in 2020 with no alcohol interaction data? The label says "avoid alcohol" but the bioequivalence report doesn’t mention it. I’ve got the redacted PDF. This is how people die. And nobody talks about it. Why? Because the system protects itself.

Freddy King

February 26, 2026 AT 08:41Let’s be real - the whole MR BE framework is a glorified game of Jenga. You pull one block - the coating thickness - and the whole structure collapses. And the stats? RSABE, partial AUC, f2, f1… it’s all just math noise. I’ve seen three identical formulations fail because one lab used a different dissolution apparatus. It’s not science. It’s theater. And the audience? Patients who can’t tell the difference between a 10% spike and a 10% drop.

Laura B

February 26, 2026 AT 22:10As someone who’s been on an extended-release seizure med for 8 years, I’ve switched generics 4 times. Twice I had breakthrough seizures. Once I was dizzy for a week. I didn’t know why - until I read this. I’m not mad at the manufacturers. I’m mad at the system that lets "bioequivalent" mean "close enough." You wouldn’t accept a "close enough" heart valve. Why accept it for your brain?

Robin bremer

February 27, 2026 AT 12:41bro this is wild 😭 i just got my new generic and it’s making me feel like a zombie… like i’m not even me anymore. i thought it was just me. turns out it’s the damn coating. now i have to go back to the brand and pay $500/month. thanks, FDA. 🤡

Jayanta Boruah

February 28, 2026 AT 06:30India produces 20% of global generic drugs. Yet, not a single Indian company has successfully launched an MR generic approved by the FDA since 2018. Why? Because dissolution testing requires precision engineering - not cost-cutting. The Indian pharmaceutical model thrives on economies of scale. MR drugs demand economies of precision. This is not a technical gap - it is a systemic failure of regulatory literacy.

Nina Catherine

March 1, 2026 AT 21:49Hi everyone - I’m a clinical pharmacist and I want to say: this isn’t just about data. It’s about trust. When patients switch generics and feel "off," they stop taking meds. That’s not compliance - that’s trauma. We need better communication. We need clearer labels. And we need to stop calling it "bioequivalent" when it’s clearly not clinically equivalent. Let’s rename it "statistically similar" and be honest with people. 🙏

Amrit N

March 3, 2026 AT 15:09Man I used to work in a pharmacy. People would come in mad because their new generic made them sleepy or jittery. We’d say "it’s the same thing." But now I know - it’s not. The beads are different. The coating is thinner. The release curve is shifted. We were lying to them. And they paid for it with their sleep, their focus, their stability. I’m sorry.

Courtney Hain

March 4, 2026 AT 09:11Think about this: the FDA approved 12 MR generics using IVIVC models - meaning they skipped human trials. But what if the model is wrong? What if the lab conditions don’t match real stomach pH? What if the patient has gastroparesis? We’re letting algorithms decide if someone lives or dies. And we call this innovation? This isn’t science - it’s a bet. And the house always wins.

Robert Shiu

March 6, 2026 AT 01:36For anyone wondering why this matters - imagine your insulin pump suddenly changed how fast it delivers. Not the dose. Not the total. Just the timing. One minute late could mean a seizure. One minute early could mean a coma. That’s what we’re doing with MR drugs. This isn’t about big pharma or generics. It’s about making sure the medicine works like it’s supposed to - for every single person. No exceptions.